(This was one of my favourite pieces I ever wrote for the old House of Glib and I thought I'd repost it rather than write whatever lame bullshit I'd come up with in the 3 hours before I have to go to work. At the end there's the promise of future updates in the series. There's one more I did write that I probably will repost soon, but don't wait for anymore after that. Ain't gonna happen.)

The thing about being in last place is that it allows you to take risks you would never even consider if you were winning the race. After all, what do you have to lose? If your risk succeeds, then you've made yourself a winner, and if it fails, you're no worse off than you were in the first place.

In 1980 Fred Silverman had been the president of the last place National Broadcasting Company (NBC) for two years--a position he had earned thanks to his reputation as a man who could work miracles for any network he worked for. During his tenure at the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), he had moved the network away from its core of rural comedies (

Mayberry R.F.D, Green Acres, The Beverly Hillbillies and

Hee-Haw) and transformed it into the home of much more sophisticated comedies such as

All in the Family, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Bob Newhart Show and

M*A*S*H. At the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) he inherited an ailing

Happy Days and not only turned it into a top-rated hit, but built on its success with the popular spin-offs

Laverne and Shirley and

Mork and Mindy. He also gave the greenlight to such future hits as

Barney Miller, Fantasy Island. Three's Company and

Charlie's Angels, taking the network from last to first place.

Now it was his turn to revive NBC, but unfortunately the magic he once seemed to have possessed appeared to have finally run out. Instead of putting out hits, he gave the world Supertrain, B.J. and the Bear and Hello Larry. Apart from such nominal successes such as Diff'rent Strokes and its spin-off The Facts of Life, the Peacock network's schedule was such a black hole that it had taken to airing Saturday Night Live reruns on Friday nights in place of original programming. If this wasn't the time to start taking some risks, then what was?

Enter the duo of two Canadian-born Greek brothers who had a contractual commitment to deliver a new variety show to Silverman's network. Sid and Marty Krofft had made their fortune as the creators of a series of imaginative Saturday morning TV shows that took full advantage of their background in puppetry. After beginning their producing careers with the cult classic H.R. Pufnstuf in 1969, they spent the first part of the decade entertaining children before finally deciding to move on to prime time fare with the Osmand siblings' 1976 variety show, Donny and Marie. Unfortunately they followed this success with one of TV's most infamous debacles, 1977s The Brady Bunch Hour--a legendary flop in which the fictional Brady family moved away from their suburban home to Hollywood, so they could host their own truly terrible variety show. Not quite as infamous, but equally lamentable was their attempt to turn a group of Scottish one hit wonders into TV stars with 1978s The Bay City Rollers Show--a series derailed by a) the group's utter lack of comedic (and musical) talent, b) accents so thick they made their poorly delivered punchlines completely unintelligible and c) its being filmed after the highly-acrimonious group had essentially split up and were no longer speaking to each other. Despite these failures, the Krofft's were determined to hold onto their new variety show niche and in 1980 they delivered to NBC not one, but two such efforts.

(Now, those of you who have some clue where I'm going with this already know I'm not about to start talking about Barbara Mandrell and the Mandrell Sisters....)

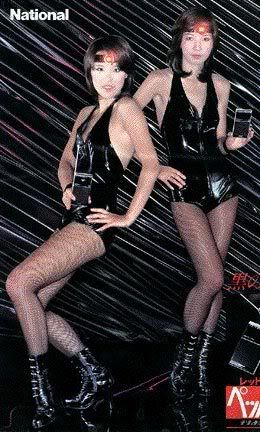

In the beginning, the Krofft's considered Hee-Haw's Roy Clark as a potential host and then very briefly considered The Village People, before being told that NBC had made a deal with a Japanese company involving the cross-promotion of their various entertainment projects. As part of that deal, NBC was obligated to air six hours of content featuring a property owned by the Japanese company. Among these potential properties was a megasuccessful female singing duo who had sold over 100,000,000 albums in Japan since 1976 and who had just made their first attempt to break into the North American market with the minor hit single "Kiss in the Dark" (which peaked at #37 on the Billboard Top 40).

Silverman and his fellow executives were too beaten to care how they met their Japanese obligation and their foreign counterparts desperately wanted to counteract the duo's waning popularity at home by making them superstars in North America, so the Krofft's were told that they could meet their final commitment to the beleaguered network by producing six episodes of a variety show starring the duo and the two brothers--happy to have the difficult decision taken out of their hands--agreed.

And thus Pink Lady was born.

To direct the series' "comedy" segments, the Kroffts hired frequent Mel Brooks collaborator Rudy De Luca, who would later go on to write and direct

Transylvania 6-5000, a 1985 horror movie satire only remembered today because it featured a young Geena Davis in an ultra-fetching vampiress costume three years before she won the Oscar for

The Accidental Tourist. To handle the writing of the show, they turned to

Mark Evanier, who had worked on the lamentable Bay City Rollers show and who would go on to earn comic book immortality thanks to his collaborative efforts with Sergio Aragones on

Groo the Wanderer.

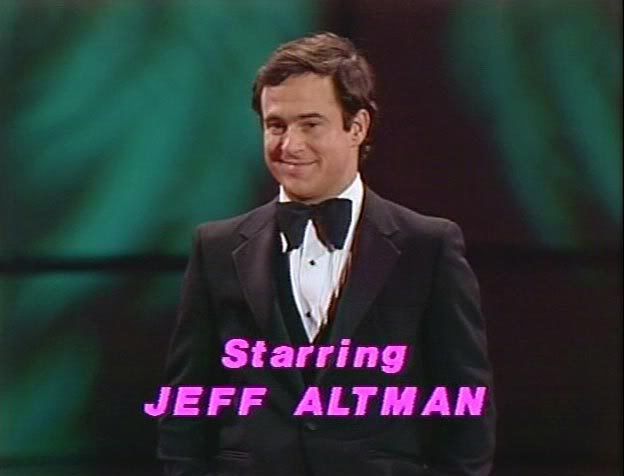

Knowing that they would need a western face to absorb the potential culture shock of a network show hosted by two Japanese woman, they hired a 29 year-old comedian who had a development contract with NBC at that time--Jeff Altman. In later interviews, Altman would (only half-jokingly) suggest that he got the job because his last name started with an "A" and was therefore at the top of the list of comedians who had similar deals with the network.

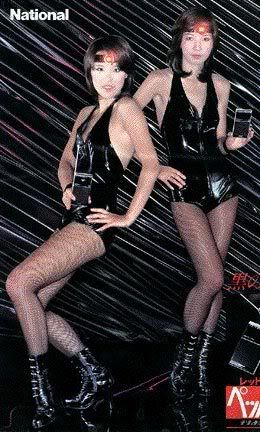

Unfortunately for the behind the scenes talent, the extremely tight schedule of their foreign stars did not allow them to meet or rehearse with the duo until the day before the pilot episode was scheduled to be shot. It was only then that they learned the two details that ensured the entire project had been doomed from conception. Despite the constant assurances to the contrary, Mitsuyo Nemoto (aka Mie) and Keiko Masuda (aka Kei) were not fluent in English. Though they could engage in extremely limited conversation, they definitely did not speak the language well enough to host a North American TV show. To make matters worse, it was clear that neither one of them wanted to have anything to do with the show and were doing it out of contractual obligation rather than professional desire.

The end result was an infamous trainwreck that is rightfully considered one of the worst TV shows of all time; one that remains as perhaps the best example of a "What Were They Thinking?" failure that era ever produced.

Six episodes were filmed in total, all of which are available on DVD (the show's lamentable reputation having grown large enough over the years for it to become a desirable collectible for all lovers of show business kitsch) and all of which I now have in my possession. For reasons I still don't quite yet understand myself, I have decided to review each one of these six episodes--a task that will no doubt require a Herculian amount of will and endurance. Enough so that I have chosen to name the endeavor the very first:

House of Glib Challange!

Today I shall begin with the pilot episode mentioned above. Having just watched it and listened to

this Realaudio interview with Mark Evanier, in which he implies that it rose to a level of success the others could not meet, I truly understand what a painful and agonizing task I have set for myself. I sincerely hope that the end results justify whatever pain I will surely experience.

Episode One

"It Begins...."

Guest Stars:

Sherman Hemsley

Bert Parks

and

Blondie

The credits begin with shots of a stadium full of people, all of them presumably there to worship our lovely young hosts. Mie and Kei are shown waving to their hoards of adoring fans as they drive to their stage in the backs of separate convertibles (because sharing one would be so gauche!)--pink chyrons informing us who these presumably famous women actually are. This is followed by a credit shot for Altman and then, oddly, another one for our titular hosts--a move that essentially gives them both first and third billing. My guess is that they did this to remind the less capable viewers who weren't paying attention five seconds earlier that the two Japanese girls actually are supposed to be the stars of the show. The credits continue, giving us a chilling look at the next 46 minutes of our lives.

Altman comes out alone--the ovation he receives baring no possible relation to the amount of people sitting in the theater. Despite there being at most 100 people hijacked tourists annoyed that they couldn't get in to see a good show surrounding the stage (and I'm being generous with that figure) the sound we hear is equivalent to the applause and cheers of a packed auditorium. The same aural disconnect is evident as Altman begins his monologue and is met by laughter that is far too powerful for both that amount of people and the actual quality of the jokes. As a stand-up, Altman has always been more of a character comedian--relying on impressions and funny voices for his laughs--so he seems visibly uncomfortable as he tells a series of sub-sub-Carson one liners and only seems happy after pulling off an out-of-place pratfall. Following his slapschtick, he goes on to introduce his co-hosts, explaining to the audience that despite their relative anonymity in North America, they are HUGE in Japan. He proves it by showing the exact same stadium footage we were treated to in the credits three and a half minutes earlier. The subtext might as well be text--THESE GIRLS ARE SUPERFAMOUS, so it doesn't really matter if you have no fucking clue who they are. Altman informs us that Mie and Kei are going to begin the show by performing "...what I've been told is a traditional Japanese number," and the two of them come out in ornate kimonos, which--following a brief Japanese-language intro--they tear off to reveal glittery pink gowns as they begin singing their version of Earth, Wind and Fire's disco classic "Boogie Wonderland".

Now is as good time as any to discuss Pink Lady's musical abilities--they're not terrible, but one cannot help but assume that they're much, much better when performing in their own language. Though their version lacks the funky beauty of the original, it is fun in a goofy karaoke kind of way. Unfortunately the same could not be said for the dancing that accompanies it.

In his interview, Evanier tells us that the only time the ultra-professional duo ever got mad during the whole ordeal was when they felt they weren't given enough time to perfect their dance moves. Having much more pride in their dancing ability than their singing, they worried that the scant rehearsal time they were given was making them look bad and they had a point. Not only do their movements seem under-rehearsed, but so do those of their back-up chorus, whose out-of-sync mistakes the camera completely fails not to highlight at every opportunity.

Their first number having come to its inevitable conclusion, it's finally time to see how Pink Lady fare in the non-lip-syncing portion of the show. It's at this point that you actually start feeling some empathy and affection for our embattled heroines as you imagine how you would do if you were asked to attempt to get laughs via a phonetically memorized script written in a language you don't understand that's filled with specific cultural references and attitudes that bear no relation to your life experience. By that standard, Mie and Kei actually do an admirable job, although it certainly helps that they are both far more adorable than you or I will ever be (no offense, but it's totally true). From the very beginning it becomes clear that the writers are following the mold of past variety hits such as The Sonny and Cher Show and Donny and Marie, by attempting to give each host their own distinctive personality. Mie is the polite, hospitable one, Altman is the stooge who's constantly trying to make himself seem more successful than he actually is and Kei is the sarcastic bee-yotch who isn't afraid to put her male co-host in his proper place.

Naturally, this instantly makes Kei our favourite.

Despite their best efforts, the trio's success is severely hampered by the quality of their material, which seems as though it would have appeared dated even when it first aired, much less 27 years later. One of the more cringe-worthy elements of the show are the constant Japanese references, which err on the wrong side of insulting stereotype. At the end of their banter, the girls introduce Altman to their "bodyguardo", a fat guy posing as a sumo wrestler wearing a much-more network-friendly version of the traditional mawashi.

Click to Enlarge

After returning from what was presumably a much-welcome commercial break, Mie and Kei start singing a song in front of a set designed to look like a large portable stereo (with a blue-screened image of a real stereo used in the long shots). It's hard to tell, but it appears the song has something to do with the kind of things you are likely to hear on the radio and is merely a ruse to connect together a series of random and universally unfunny blackout sketches, all of which seem to be designed to showcase Altman's character skills. The first sketch has him portraying a radio evangelist, but any potential satire of such folks is dutifully avoided so as not to alienate the Southern folk who might not see the humour in such mockery. The second features Leonard Moon, the punch-drunk boxer who regularly appeared in Altman's stand up work. Beyond that it's only noteworthy for featuring a foxy 70s redhead in a slinky dress (for absolutely no discernible reason besides the fact that such creatures are admittedly fascinating to behold) and this itself is only noteworthy because when you search the credits to find out who the redhead is, you discover that none of the featured sketch performers are identified by name, which you suspect they were mad about when the show was made, but a lot less so when it actually aired.

But it is the final sketch that disappoints the most, simply because it is the only one that actually had any potential. In it Altman dances on stage doing his passable Nixon impression (which admittedly he's doing at a time when everyone--including the five year old version of me who was alive when the show was made--could do a passable Nixon impression) as the announcer--also Altman--tells us that the disgraced former president is traveling around the country as the lead singer of The Richard Nixon Soul Review. Not a brilliant or particularly insightful concept to be sure, but still one that could be funny if done right. Unfortunately the sketch ends just when it should begin, stopping short of actually showing us Tricky Dick giving us his Motown best. That the show squanders the lone idea that actually might have been successful pretty much sums up the entire state of the whole enterprise.

Click to Enlarge

Now it's time for one of the promised guest stars to finally appear. In this case it's the star of the TV classic The Jeffersons:

Sherman Hemsley!

Yeah....

Actually I have to admit that I've developed a certain fascination with the actor ever since I saw him in one the more recent iterations of The Surreal Life. Seldom as viewers have we ever gotten to see such a dramatic dichotomy between a performer and his most famous role. An actor made famous playing a loud, obnoxious blowhard (a character who was in fact designed to be a--much more successful--black Archie Bunker), Hemsley proved himself to be an extremely shy, lonely man who was so softspoken that the few times he did say something, his nearly inaudible words had to be subtitled so we could appreciate them. This has absolutely nothing to do with the topic at hand, but I suspect I'm never going to mention him on this blog ever again, so I might as well document my observation while the opportunity presents itself.

Hemsley appears in aid of a one-joke sketch that imagines what a USO show would be like if women were drafted into the military. According to the show's writers it would be exactly like a regular USO show except the comedians would be dames and the sex kittens would be dudes. Not quite what I would call a dazzling expression of the depths of the human imagination. The sketch is only significant because a) it's far longer than it has any right to be, b) it features the foxy 70s redhead mentioned above in the role of the female Bob Hope substitute and c) in it (at precisely 18 minutes and 56 seconds into its running time) we are subjected to the show's first sushi joke, which is delivered extremely awkwardly by Kei (it being obvious that both she and her partner are far better at banter than sketch-work).

Click to Enlarge

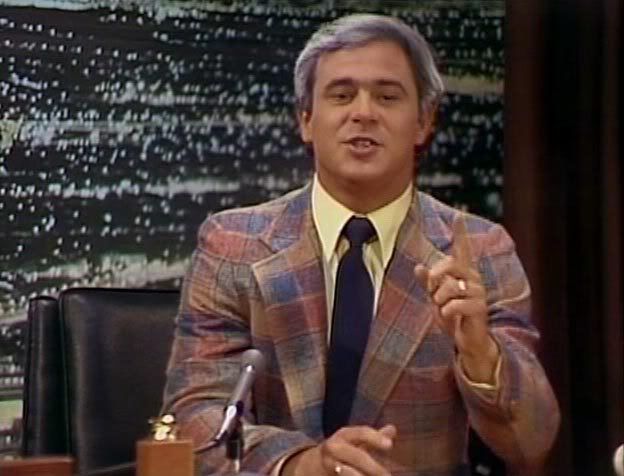

Back from another sadly nonexistent ad break (this being the rare TV DVD where the lack of commercial interruptions is a bad thing) Altman introduces the girls to their second "special" guest:

Bert Parks!

Who?

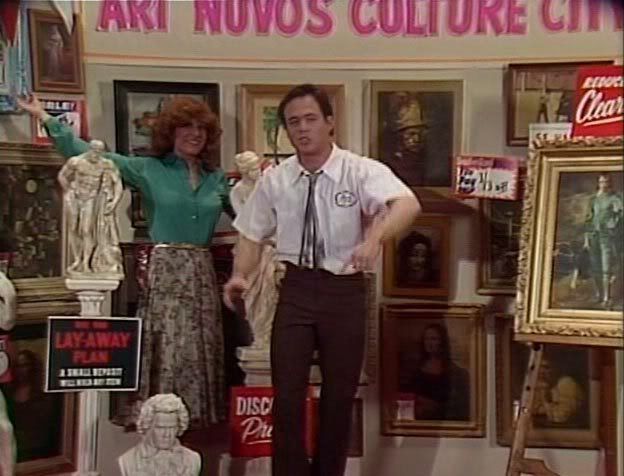

Actually, I'm enough of a show business trivia geek to know who Parks is, but--luckily for those folks my age and younger who've never heard of the dude--Altman explains who he is to the girls (he's the guy who hosted the Miss America pageant for 25 years--from 1954-1979). To the girls' amazement, the elderly gentleman's obvious stunt double tumbles onto the stage with a series of flips before a not-very-cleverly-hidden edit allows Parks to reveal himself to the audience (whose reception is still far-greater than the sum of their numbers). The necessary banter is exchanged and we cut to another sketch featuring Altman as a fast-talking "Crazy Eddie"-type shilling cultural knock-offs (who also introduces a very short and utterly inexplicable sketch featuring Altman doing a bad Marlon Perkins impression) while the foxy 70s redhead does her best busty showcase model acting in the background.

Having seen the above screencap of the foxy 70s redhead I keep referring to, I suspect several of you are thinking "Dude, she's not that foxy--move on already!" To which I can only respond by saying:

Too late!

I am already smitten

and

I cannot be unsmit!

It finally being time for us to see something that doesn't suck, the show cuts to a video of Blondie performing the fourth track "Shayla" from their 1979 album Eat to the Beat (and anyone who tells you that the only reason I know this is because I just spent the last ten minutes browsing through their catalog on iTunes is a dirty rotten stinking liar who should mind their own beeswax thank you very much!). Based on a quick peak at the rest of the episodes, it appears as though any musical act that actually had the slightest bit of "heat" in 1980 made their appearances via pre-taped videos that spared them the indignity of interacting with the hosts. In the case of Cheap Trick, their "appearance" in the third episode is actually just the music video they filmed for "Dream Police" (from the album of the same name). My guess is that when Ms. Harry and her cohorts filmed the clip, they had no idea where or how it was going to be used.

Sucks to be them!

Click to Enlarge

Back to the actual show, Altman and the girls briefly assault us with a sketch called "The Adventure of the Pink Falcon", which one assumes is a reference to The Pink Panther series, but really only seems to exist to prove that a) Mie looks better in a vinyl jumpsuit than Kei does and b) Altman cannot do a proper Bogart impression to save his or anyone else's life.

Fortunately the sketch is short and cuts to a longer piece in which Altman does a bad Carson impression and interviews the girls--thus allowing them to be identified via chyron for the third time this episode. Somebody really wants to make sure that we know who these girls are! Before the sketch ends with a joke whose sole premise is that a comedian performing in Japanese is hee-larious, we are exposed to what amounts to be the most entertaining 13 seconds of the entire show (and probably the entire series):

Click to Enlarge

The last desperate volley of sketches comes in the form of a tribute-of-sorts to Hollywood. Despite his present-day obscurity, one does have to admit that Parks is an old pro and has far more talent than a show like this deserves--his introductory song and dance actually bordering on the right side of charming rather than the more likely cheesy and dated. Hemsley makes his final appearance in a sketch that takes aim at overtly-political Oscar speeches (take THAT Vanessa Redgrave!) and sign-language captioning for the deaf (take THAT...uh...deaf people....), but that I'm only mentioning because it has foxy 70s redhead in it. I'd describe the rest of the sketches but this post is already four times longer than I thought it would be, so I'll merely say that they suck harder than yo mama (take THAT yo mama!) and move on to the song and dance medley that ends the show.

A song and dance medley ends the show.

Following some banter involving Neil Diamond (in which he is not used as a punchline) the girls perform snippets of Carol King's "You've Got A Friend", Fleetwood Mac's "Don't Stop" and Eddie Floyd's "Knock on Wood". But don't take my word for it, see it for yourself:

Click to Enlarge

And--FINALLY!--we reach the end of the show, which Mie and Kei inform Altman means it's time to go into the hot tub! Our American co-host protests, but the girls change out of their dresses into string bikinis and drag him--tuxedo and all--into the hot tub, where he still protests, but with far less enthusiasm and conviction. Now would seem like a perfect time to reintroduce a forgotten character from the beginning of the show!

Oh, that "bodyguardo"!

He's so fat and naked!

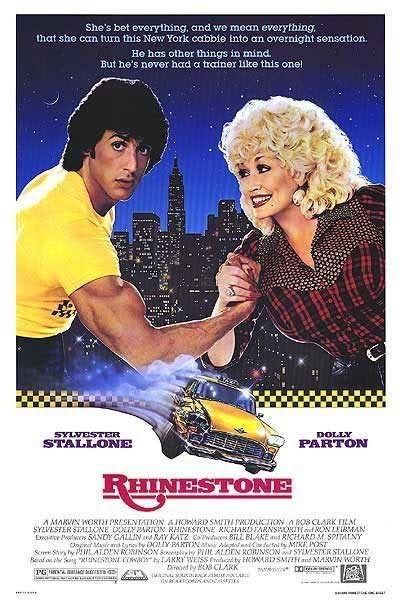

And with that the credits role and I feel a shiver roll down my spine knowing that I have to do this five more times and next time I'll have to face this:

Pray for me!

In 1980 Fred Silverman had been the president of the last place National Broadcasting Company (NBC) for two years--a position he had earned thanks to his reputation as a man who could work miracles for any network he worked for. During his tenure at the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), he had moved the network away from its core of rural comedies (Mayberry R.F.D, Green Acres, The Beverly Hillbillies and Hee-Haw) and transformed it into the home of much more sophisticated comedies such as All in the Family, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Bob Newhart Show and M*A*S*H. At the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) he inherited an ailing Happy Days and not only turned it into a top-rated hit, but built on its success with the popular spin-offs Laverne and Shirley and Mork and Mindy. He also gave the greenlight to such future hits as Barney Miller, Fantasy Island. Three's Company and Charlie's Angels, taking the network from last to first place.

In 1980 Fred Silverman had been the president of the last place National Broadcasting Company (NBC) for two years--a position he had earned thanks to his reputation as a man who could work miracles for any network he worked for. During his tenure at the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), he had moved the network away from its core of rural comedies (Mayberry R.F.D, Green Acres, The Beverly Hillbillies and Hee-Haw) and transformed it into the home of much more sophisticated comedies such as All in the Family, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Bob Newhart Show and M*A*S*H. At the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) he inherited an ailing Happy Days and not only turned it into a top-rated hit, but built on its success with the popular spin-offs Laverne and Shirley and Mork and Mindy. He also gave the greenlight to such future hits as Barney Miller, Fantasy Island. Three's Company and Charlie's Angels, taking the network from last to first place.

Unfortunately for the behind the scenes talent, the extremely tight schedule of their foreign stars did not allow them to meet or rehearse with the duo until the day before the pilot episode was scheduled to be shot. It was only then that they learned the two details that ensured the entire project had been doomed from conception. Despite the constant assurances to the contrary, Mitsuyo Nemoto (aka Mie) and Keiko Masuda (aka Kei) were not fluent in English. Though they could engage in extremely limited conversation, they definitely did not speak the language well enough to host a North American TV show. To make matters worse, it was clear that neither one of them wanted to have anything to do with the show and were doing it out of contractual obligation rather than professional desire.

Unfortunately for the behind the scenes talent, the extremely tight schedule of their foreign stars did not allow them to meet or rehearse with the duo until the day before the pilot episode was scheduled to be shot. It was only then that they learned the two details that ensured the entire project had been doomed from conception. Despite the constant assurances to the contrary, Mitsuyo Nemoto (aka Mie) and Keiko Masuda (aka Kei) were not fluent in English. Though they could engage in extremely limited conversation, they definitely did not speak the language well enough to host a North American TV show. To make matters worse, it was clear that neither one of them wanted to have anything to do with the show and were doing it out of contractual obligation rather than professional desire.