(Another repost! Deal with it!)

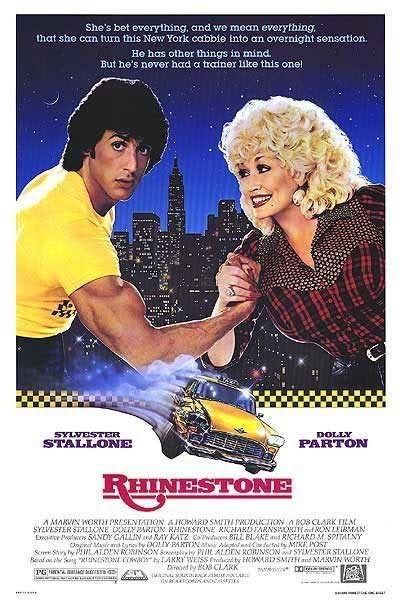

I bet if I were to ask even the sharpest of movie freaks to compose a list of performers most closely associated with that glorious enterprise known as the Bad Seventies Musical it would take quite a long while for the name Sylvester Stallone to eventually come up, but the truth is that the Italian Stallion has not one, but two such memorable disasters hidden away amongst the many lunk-headed sequels, misguided comedies and action flops that dominate much of his filmography. The second of these two,

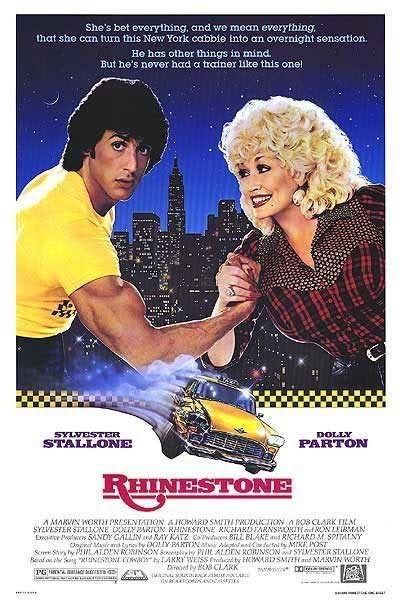

Rhinestone (in which he played a

monosyllabic New York cab driver who Dolly Parton bets she can transform into a Country Music star) is the more obvious of the two, since he actually stars in it and is as horrifyingly bad as you would imagine, but the first is far more important since it is the film that marked the true turning point in his career.

Looking back with the gift of hindsight and the knowledge of all the truly terrible films to come (

Rhinestone,

Rocky IV,

Cobra,

Over the Top,

Rocky V,

Stop Or My Mom Will Shoot!,

Judge Dread and

Driven to name just the most purely wretched of a wretched bunch) it seems odd to read Roger Ebert describe the subject of today’s post as “…the first bad film [Stallone has] made,” but people forget that following his star-turning breakout in the Academy Award-winning megahit

Rocky, there was a period where Stallone was actually considered a gifted actor and filmmaker (as incredible as it seems he not only had been nominated for Best Screenplay, but Best Actor as well).

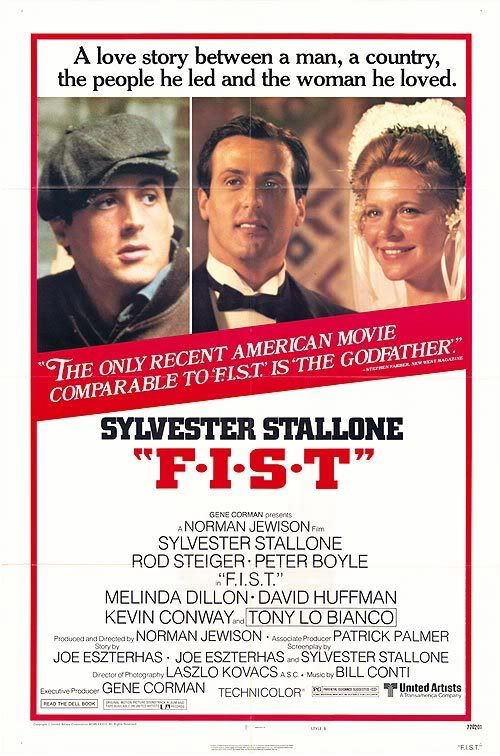

After

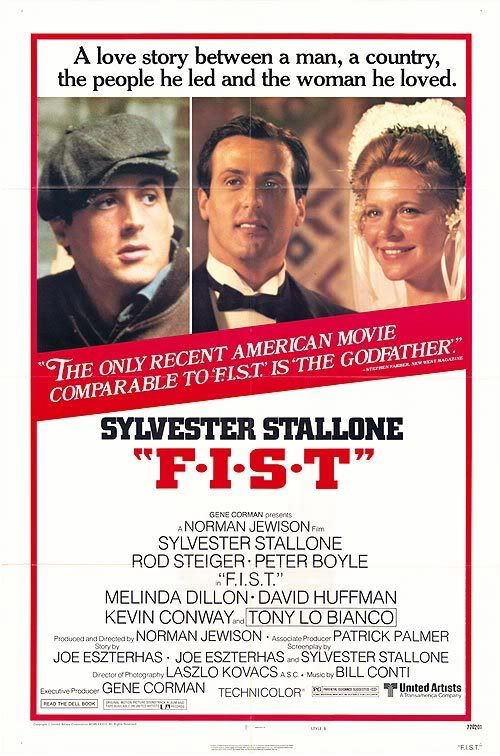

Rocky he co-wrote the screenplay (with the infamous Joe Eszterhas, who made his own contribution to the world of Bad Seventies Musicals with his screenplays for

Flashdance and

Showgirls) and starred in Norman Jewison’s union drama

F*I*S*T, which wasn’t nearly as well received, but kept afloat his reputation as a serious actor and writer who had the potential to be one of the great talents of the decade. The same was true for the period wrestling drama

Paradise Alley, which also marked his directorial debut.

Rocky II, which he also directed, proved to be a much bigger hit and though the general consensus was that it was inferior to the original, both critics and audiences seem to agree that it was still a well-made and entertaining film. After that Rutger Hauer’s villain got most of the attention from

Nighthawks and North America’s indifference to soccer kept

Victory from being a hit, but the back-to-back smashes of

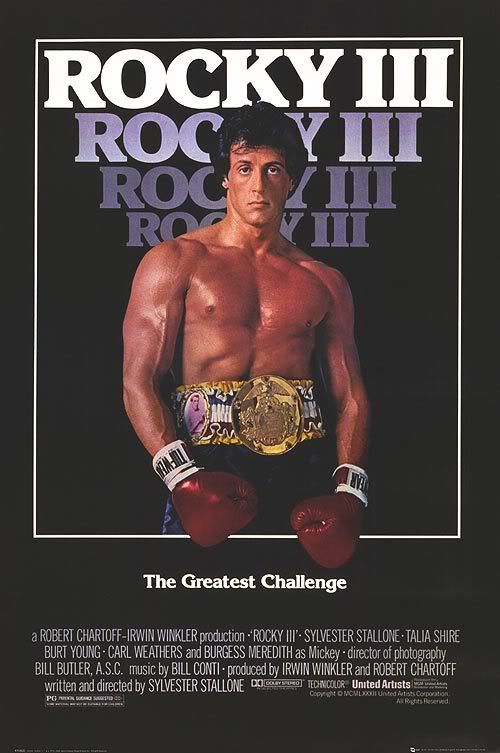

Rocky III (which he wrote and directed) and

First Blood (which he did not) truly made it seem like Stallone was a man with the Midas touch. True, there were some rumblings that he had taken the

Rocky franchise into a strangely cartoonish direction that seemed far removed from the sweet, realistic drama of the original, but even this could be deemed excusable when you considered that the first film was about a no-name boxer who dreamed of being the champ and the third was about a champ who had already gotten everything he had ever wanted.

It was a position Stallone could write about from personal experience, having gone from a bit-part actor struggling to pay his rent to a superstar who now had the professional freedom to do whatever he wanted. And what he wanted to do in 1982 was make the transition towards becoming a pure filmmaker—one who could make the movies he wanted without having to star in them as well.

This was not as simple as it sounds. Though by this time Clint Eastwood (an actor turned director whose reputation for minimalist performances and cheesy patriotic action movies was at one time almost identical to Stallone’s) had already directed nine films, he had only failed to star in one of them and it, Breezy, remains the most obscure film he has ever made. Decades earlier, Gene Kelly made three films purely as a director, but the only one people remembered was Hello Dolly, an infamous financial fiasco. And Jack Lemmon’s sole directorial effort, Kotch, told a tale not unlike the one found in Breezy—with just as memorable results.

At that time Robert Redford had been the only superstar actor to successfully make the transition to non-performing director with his debut Ordinary People. But unlike Redford, who used his clout to get a downbeat and commercially questionable film made with the actors he wanted (rather than ones he thought would sell tickets), Stallone decided that for his first film completely behind the camera, he would instead craft a sequel to the huge 1977 hit film that had made John Travolta an overnight star and taught the world the glory of the discothèque.

I am, of course, talking about:

STARRING

John Travolta as Tony

A Struggling Dancer

Cynthia Rhodes as Jackie

Another Struggling Dancer

Finola Hughes as Laura

A Successful Dancer

Sylvester Stallone as Random Asshole On the Street

A Random Asshole On the Street

And

Frank Stallone as Carl

A Rhythm Guitarist

PLOT

(OR LACK THEREOF):

Back in Brooklyn in 1977, Tony Manero was the king of the disco, but six years later he’s just another out of work dancer in Manhattan, making ends meet teaching classes to untalented wannabes and waiting tables at the kind of club he used to rule. Thanks to his only slightly more successful friend and occasional bedmate Jackie, he meets Laura, a wealthy British dancer whose moves and “intelligent” accent instantly catches his interest. When he is cast in the chorus of her new show, Satan’s Alley, he manages to spend half a night in her bed, but quickly learns that she has no interest in a man who can’t do anything for her or her career. Torn between the bitch who won’t have him and the saintly girl who will, Tony risks ruining his first big break, but when the director decides to take a chance and have him replace the show's male lead, he learns who he really is and is finally able to decide who he really loves.

MUSICAL NUMBERS:

As a “behind the scenes” musical, Staying Alive eschews the traditional break-out-into-song-and-dance scenes in favour of the kind of musical montages popularized by the success of Flashdance, but best exemplified by the extraordinary “On Broadway” sequence in Bob’s Fosse’s All That Jazz. That said, the following scenes certainly do qualify:

SNARKY DECONSTRUCTION:

Assuming you merely scrolled down past the above list in a hurried attempt to get to this post's chewy, snarky center, I think it would behoove you to quickly look at it one more time and see if you notice an odd pattern forming. While you take care of that, I'll just insert a jpeg of a magazine cover from this period that does little to downplay the long-held rumours of Travolta's closeted homosexualty:

Ready now? Okay, then I'm sure you noticed that of the six musical numbers noted above, half feature songs performed by the director's infamously less-successful younger sibling, Frank. What you probably didn't note--because it's the kind of information no sane person should actually know off the top of their heads--is that the remaining three numbers feature songs that were written by Frank Stallone as well. This is not insignificant, as it is the clearest example of the level of hubris Stallone possessed as he worked on the project.

Lemme explain.

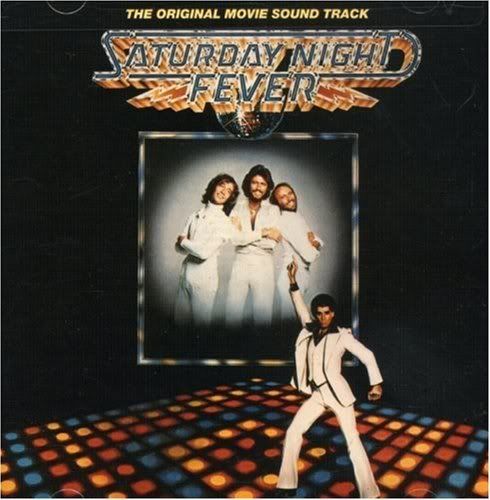

As iconic as Tony Manero's white suit was, it was three brothers from Australia who were truly responsible for turning a movie about an asshole who likes to dance into something much, much more. It has become popular now to praise Saturday Night Fever the film as a classic example of how the 70s cinematic pursuit of verisimilitude was able to transform a typical teen dance movie into a major work of art--to the point that it more resembled a work of cultural anthropology than any mere trifling entertainment. On the other hand, the popular opinion of Saturday Night Fever the record album is that it is one of the archetypal examples of the wretched tastelessness that defined the end of the lamentable me-decade--a craven musical sell out from a group once best known for folky pop songs with memorable harmonies. What this clearly ignores is that while the film was a popular success, the album was a zeitgeist-changing uber-phenomenon. By the time they got around to filming Staying Alive (which itself was named after the album's biggest hit) the soundtrack recorded by the brothers Gibb still held the record for best selling LP of all time, having gone platinum 15 times over since its release. It wouldn't be until a year after Staying Alive bombed that Michael Jackson's Thriller would finally best the Bee-Gee's achievement.

What some folks might not realize is that this was not an accident. Saturday Night Fever was produced by an Australian gentleman named Robert Stigwood, who at that time was best known as the manager of a group of singing brothers known as--you guessed it--The Bee-Gees. It should come as no surprise then that his principal interest in the project wasn't in presenting an anthropological study of the social rituals of Brooklyn douchebags, but rather in crafting the perfect comeback vehicle for his biggest meal ticket. Rather than the album being a fortuitous offshoot of the film, the film was made specifically to justify the creation of the album.

But that had been over five years ago--a lifetime in the world of music--and The Bee-Gees had become the Celine Dion's of their time, a group no one with even the tiniest iota of taste and/or self-awareness could admit to enjoying. Because of this Stallone recognized that the group's music would have to be featured in the film, but it could not be allowed to dominate. Thanks to Stigwood's role as the film's producer, the group received prominent billing in its opening credits, but--with the exception of the use of the title song at the very end--the truth is that their contributions amount to little more than anonymous background filler. Rather than rely on the music of the group that allowed for the first film's creation and massive cultural success, Stallone chose to ignore it in favour of the questionable efforts of his baby brother, who he also cast in the not-so-crucial role of the guitar player in Jackie's band.

I could spend a good long while discussing the reasons why he would choose to do something so obviously foolish, but in the end the only one that matters is the simplest--because he could.

As reasons justifying disastrous decisions go, "Because he could," is probably responsible for destroying more careers than any other in Hollywood. As any proper student of cinematic failure can tell you, there are two distinct kinds of Hollywood flop--the corporate folly and the vanity project--and in most cases the ultimate blame for their failures can both be attributed to "Because he could," the only variable being just who the "he" in the equation is. With the exception of perhaps Eddie Murphy, no other iconic 80s superstar suffered more as a result of his ability to make his decisions without having to justify them to the people signing his massive paychecks. Unlike Bruce Willis, who could survive and thrive after a "Because he could" flop on the level of Hudson Hawk (a film I am proud to say I actually saw in the theater when it was released), once Stallone started failing, it became impossible for him to stop. Given the freedom to do whatever he wanted with a project that had nothing to do with Rocky Balboa or John Rambo, he proved that his less-than-stellar vision would lead to him attempting to turn his brother into The Next Big Thing, regardless of whether or not Frank had the talent to justify it.

For this reason Staying Alive is important as the turning point in Stallone's career. Despite his only appearing onscreen for a couple of seconds, its failure laid the groundwork for all of his other failures to come.

That said, I have to admit that the music provided by Frank Stallone does amount to being the high point of the film, for as cheesy as it may sound, it's downright revolutionary compared to the film's script.

What Stallone and Norman Wexler, Staying Alive's two credited writers, didn't seem to realize is that if you choose to forgo plot in favour of a more intimate character drama, you are then required to create interesting three-dimensional characters who are compelling enough on their own to make you forget the utter lack of story. Instead they crafted a screenplay inhabited by cyphers whose actions are entirely dependent on what the director wanted to have happen in each scene, rather than what they would actually do in that situation.

But more than that, the screenplay fails because the director is never able to convince us that its logical conclusion is at all valid.. According to the script, we are supposed to come to believe that while Laura is initially compelling, her ambition and self-devotion make her unworthy of Tony's affection, while Jackie's ability to forgive his trespasses and love him for who he is makes her the deserved choice.

This may have flew in 1983, but 25 years later, it reeks of old-fashioned sexism. Laura's faults are no different than Tony's, but because she's a woman they are deemed unseemly, while Jackie's strange willingness to be continually treated like a doormat is portrayed as her most noble quality, rather than the tragic weakness it is. It doesn't help Stallone's cause that Finola Hughes is so much more interesting and charismatic than her blond counterpart, Cynthia Rhodes (whose greatest contribution to pop culture remains her performance as the girl whose botched abortion compels Baby to dance with Johnny in Dirty Dancing). Perhaps Stallone wanted to make a point about how settling for mediocrity is the fate of everyone, even gifted dancers, but if so he does not properly sell this conclusion and instead leaves the viewer hating Tony even more than they already did for settling for someone as challenging as a People magazine crossword puzzle.

THE KINDA-GAY PART:

What then is there about Stallone's first major folly to make it worthy of the attention of the second Project Kinda-Gay post? Well, as strange at it may seem, for all of his vanity and undeserved egomania, Stallone was a filmmaker who wanted to stretch beyond the limits of his comfort zone and the proof of this lies in Staying Alive's existence. And though its failure doomed him to direct only the sequels and "reboots" of his two most profitable franchise, there is something honourable in the attempt--even considering how poorly that attempt ending up being.

Anyone can do what they're good at and continue to succeed, but it takes a brave soul (albeit a brave foolish soul) to try something different and risk embarrassing themselves in the process. Stallone in this instance was that brave foolish soul and for that he derserves to strut:

monosyllabic New York cab driver who Dolly Parton bets she can transform into a Country Music star) is the more obvious of the two, since he actually stars in it and is as horrifyingly bad as you would imagine, but the first is far more important since it is the film that marked the true turning point in his career.

monosyllabic New York cab driver who Dolly Parton bets she can transform into a Country Music star) is the more obvious of the two, since he actually stars in it and is as horrifyingly bad as you would imagine, but the first is far more important since it is the film that marked the true turning point in his career. After Rocky he co-wrote the screenplay (with the infamous Joe Eszterhas, who made his own contribution to the world of Bad Seventies Musicals with his screenplays for Flashdance and Showgirls) and starred in Norman Jewison’s union drama F*I*S*T, which wasn’t nearly as well received, but kept afloat his reputation as a serious actor and writer who had the potential to be one of the great talents of the decade. The same was true for the period wrestling drama Paradise Alley, which also marked his directorial debut. Rocky II, which he also directed, proved to be a much bigger hit and though the general consensus was that it was inferior to the original, both critics and audiences seem to agree that it was still a well-made and entertaining film. After that Rutger Hauer’s villain got most of the attention from Nighthawks and North America’s indifference to soccer kept Victory from being a hit, but the back-to-back smashes of Rocky III (which he wrote and directed) and First Blood (which he did not) truly made it seem like Stallone was a man with the Midas touch. True, there were some rumblings that he had taken the Rocky franchise into a strangely cartoonish direction that seemed far removed from the sweet, realistic drama of the original, but even this could be deemed excusable when you considered that the first film was about a no-name boxer who dreamed of being the champ and the third was about a champ who had already gotten everything he had ever wanted.

After Rocky he co-wrote the screenplay (with the infamous Joe Eszterhas, who made his own contribution to the world of Bad Seventies Musicals with his screenplays for Flashdance and Showgirls) and starred in Norman Jewison’s union drama F*I*S*T, which wasn’t nearly as well received, but kept afloat his reputation as a serious actor and writer who had the potential to be one of the great talents of the decade. The same was true for the period wrestling drama Paradise Alley, which also marked his directorial debut. Rocky II, which he also directed, proved to be a much bigger hit and though the general consensus was that it was inferior to the original, both critics and audiences seem to agree that it was still a well-made and entertaining film. After that Rutger Hauer’s villain got most of the attention from Nighthawks and North America’s indifference to soccer kept Victory from being a hit, but the back-to-back smashes of Rocky III (which he wrote and directed) and First Blood (which he did not) truly made it seem like Stallone was a man with the Midas touch. True, there were some rumblings that he had taken the Rocky franchise into a strangely cartoonish direction that seemed far removed from the sweet, realistic drama of the original, but even this could be deemed excusable when you considered that the first film was about a no-name boxer who dreamed of being the champ and the third was about a champ who had already gotten everything he had ever wanted.