One Too Many - Deep Throat Part II (1974)

One Too Many

Deep Throat Part II (1974)

There are some films whose value and significance only make sense in a historical context. Birth of a Nation and The Jazz Singer are probably the two best examples of this. The first virtually invented the language of feature filmmaking, while the second played a crucial role in the popularization of sound, but if you ignore this and view them only on the basis of their own narratives, they are excruciating spectacles for a modern audience. One is a racist and historically libelous celebration of the creation of the Klu Klux Klan and the second is a sentimental bore based on the talents of a performer whose charisma has not stood the test of time.

The same is true for another significant film

that is seldom mentioned in the same classes where nascent cinephiles are most likely to first encounter those two mentioned above.

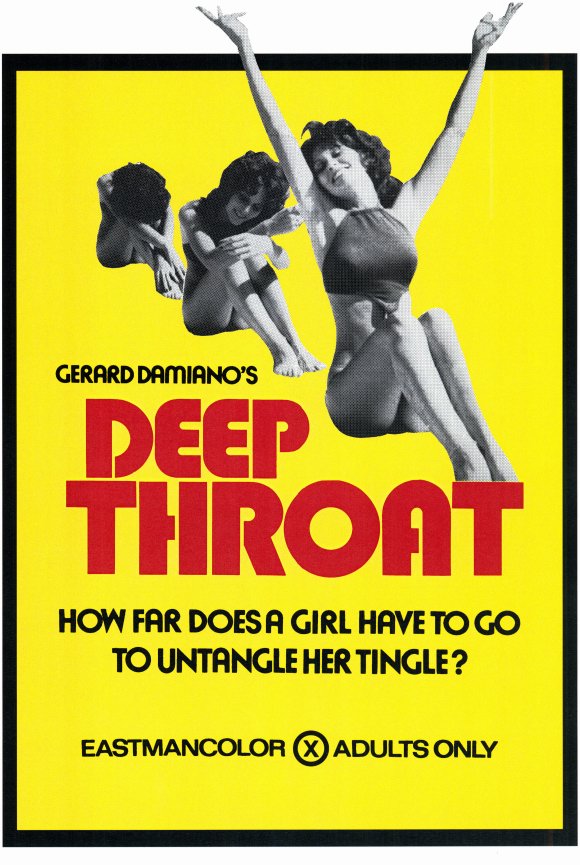

Deep Throat is a film that started a wave whose effects we still feel over four decades after its release in 1972. It could very well be the most successful ever movie made from a pure investment to profit basis (we will never know for sure, because the men who produced and distributed the film were not the sort to be open about their finances—they were the kind of men who compelled the film’s director, Gerard Damiano, to sign away his part of the profits for nothing more than the promise not to kill him).

It was the film that ushered in the wave of 70s “Porno Chic” and its popularity was closer to that of a modern “viral” YouTube video than an actual mainstream film. People went to see it because everyone else was talking about it and everyone was talking about it for a variety of reasons. Some used it to question the very idea of pornography and what that word even meant. Some used it to talk about society’s new openness to sexual experimentation after decades of repression. While many, many others used it to talk about that scene where Linda Lovelace justified the film’s title and inhaled Harry Reems’ impressive member as if it weren’t even there.

What almost no one who saw the film talked about was how good it was and that’s because—by almost every objective standard—it’s an ugly, terrible, often tedious little film. Some cult film fans will defend its sense of humour and spark of liveliness, but what they are describing is the film they want it to be, not the one it actually is.

Deep Throat is a hard film to watch for all the same reasons most pornography is hard to watch—once the negligible story (Lovelace is a young woman who has never had an orgasm, until Dr. Reems explains to her that this is because her clitoris is in her throat, meaning she can only achieve sexual fulfillment through oral sex) stops and a sex scene begins, the film becomes a badly shot and edited documentary that goes on for way too long (and—it should be said—a documentary in which Lovelace’s participation was made mandatory by the fists of her abusive husband).

Seen today, the only thing extraordinary about Deep Throat is how ordinary it is. The ubiquity of such imagery has robbed it of its power. It was the film the world needed at the time, but once that time passed, it lost all of its appeal.

But despite this, Deep Throat still has one major thing going for it—it isn’t Deep Throat Part II.

As you might have guessed, Deep Throat Part II ranks in the Blair Witch Project: Book of Shadows/Babe: Pig in the City/Grease II strata of sequel history—a film whose existence was guaranteed by the success of its originator, but which had so much going against its creation that its failure was just as equally inevitable.

Consider this. As successful as Deep Throat was financially, that success did not come without a significant price. The film and many of those responsible for its existence (including Reems and Lovelace) founds themselves being prosecuted for obscenity across the country, while legislation and ordinances were being enacted to outright ban the film and all others like it in various cities, counties and states.

There was no point in making a sequel to Deep Throat if it meant incurring that same level of legal wrath. But it seemed equally foolish not to capitalize on such a well-known brand. The trials had only done more to turn the film’s title into a household name and it’s subsequent use as the alias of Watergate whistleblower Mark Felt actually made it a part of both political AND popular history.

The solution seemed obvious. Keep the budget low and make the film R-rated. This way the gamble wouldn’t require much financial risk and there would be nothing for the nation’s self-appointed censors to prosecute. In place of Damiano, who wanted nothing to do with the film (signing contracts at gunpoint has a tendency to sour the possibility of future collaborations), Joseph Sarno—who had been making erotic features since the early 60s—was given the assignment to write and direct.

The script he produced sees Lovelace—still a nurse, as she had become in the original film—recruited by the CIA to use her charms in the name of national security. Dilbert Lamb, the programmer responsible for “Oscar”—a sentient computer database capable of keeping track of every citizen in the United States—is a neurotic nerd who has incestuous fantasies about his gray-haired aunt. The bureau hopes Lovelace’s charms will cure his sexual dysfunction and make him less of a potential liability, while the Soviets and some liberal do-gooders send their own emissaries to seduce him in order to obtain secrets and destroy “Oscar” and the invasion of privacy he represents.

Despite being made to be an R-rated film (although for years people have speculated it was actually filmed as a hardcore feature, but all of the sex scenes were cut—Sarno denied this was the case), the film’s cast was taken from the 70s porno scene (including Andrea True, an adult actress turned one hit wonder, whose catchy disco single “More, More, More” would—in the decades that followed—frequently be used as a commercial jingle, despite the fact that it’s about falling in love on a porno set). And despite ostensibly being a “mainstream” movie, Sarno made no effort to eschew his static directing style, which saw his actors reciting their lines standing beside each other in long takes while directly facing the camera.

The result is a film that looks, feels and sounds like porn, without any of the irredeeming qualities that traditionally allow us to ignore and/or abide the genre’s infamous deficiencies. Deep Throat Part II is a film that actually goes out of its way to deny the audience the one thing actually responsible for the first movie’s success. It’s a Godzilla movie without Godzilla, an action movie where no one moves, a musical without any music.

As terrible as Deep Throat is, it still served its purpose. It catered to the decade’s growing prurience at just the right moment and time. It allowed everyone to publically acknowledge that blowjobs were a thing that actually existed. On the whole, there are far worse reasons to exist. But Deep Throat Part II can claim no such virtue. It’s a film that is supposed to be sequel to a film about blowjobs that doesn’t even hint about blowjobs. It literally has no reason to exist.

And that might not have mattered if there was anything else to be found in its 88 excruciating minutes, but the entire film is a black hole of entertainment—the kind where time stands still as you watch it and each second takes on the burden of a lifetime. You will not laugh, you will not be aroused; you will only question every decision that led you to this moment.

Deep Throat is a film that only makes sense in a historical context, but Deep Throat Part II is a film that doesn’t make sense in any context. It’s a title in search of content and the content it finds has been deservedly forgotten.