Last week I finally got the chance to sit down and watch Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood, a movie I had been looking forward to seeing ever since it had been released. Whenever pressed to name my favourite film of all time, my knee-jerk answer is inevitably his third film, Magnolia, which to my mind is a work that strikes the perfect balance between emotional authenticity and cinematic fantasy. I am happy to say that Blood, his fifth film, measures up to that high standard.

Considering Anderson's great gifts as a filmmaker, I began watching the film expecting to be shocked and surprised and I was, but more so by own reaction to the material than any particular narrative twist. Having read dozens of reviews of the film, I assumed I was about to spend two and a half hours watching the tale of a charismatic sociopath—a ruthless businessman whose dogged pursuit of success at all costs eventually causes him to descend into violent madness. And I suppose I did. It’s just when the film ended and the credits began to roll, it didn’t feel as though that was the movie I had seen—simply because despite everything I watched him do, I couldn’t bring myself to hate Daniel Plainview. Not only was I able to understand why he did what he did, a part of me actually respected him for doing so. Far from being disturbed by his final act of violence, I felt more compelled to applaud it. Seldom have I been more emotionally satisfied by an act of cinematic revenge.

And I have to say that this reaction disturbed me. Plainview is clearly a terrible human being—the title of the film coming not just from the blood of the two men who die at his own hands, but all of the others whose deaths are caused by his insatiable desire for not just profit, but to also crush anyone who would attempt to compete with him for it. But as I spent much of today thinking about the movie, it occurred to me that this wasn’t the first time I had found myself sympathizing with a similarly psychotic anti-hero and—oddly enough—the film that character appeared in just happens to sit right next to Anderson’s film in my alphabetized DVD collection.

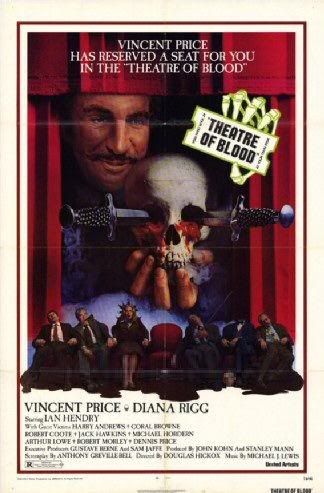

Theater of Blood is one of my all time favourite films for a number of reasons. The first of which being that it stars Vincent Price—a performer I love just as much for who he was off-camera as he was in front of it—giving what is probably his most quintessential and iconic performance. As Edward Lionheart, an aging Shakespearean actor whose success with audiences has never coincided with similar respect from the critics, Price is given the opportunity to show what he could have done in classical theater if fate had taken his career in a different direction. A famously hammy actor playing a famously hammy actor, Price manages to walk the tightrope between affecting pathos and high camp. Watching him you are instantly able to appreciate how audiences would have adored him while he earned nothing but ridicule from his critics.

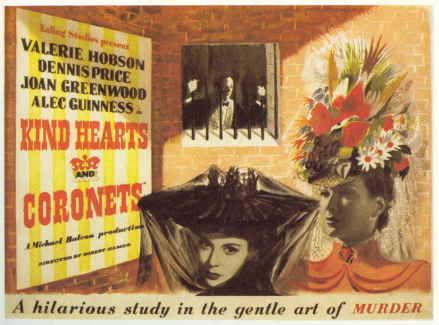

Another reason I love the film is because it is a classic British satire masquerading as a Vincent Price horror movie—a black comedy where murder is ably played for laughs because of our natural dislike for the victims, especially when compared to their much-more sympathetic executioner. In that way it is a spiritual heir to Robert Hamer’s 1949 Ealing Studio’s masterpiece Kind Hearts and Coronets—in which we eagerly cheer on a charmingly amoral shop clerk whose ascent into the aristocracy is hastened by his lethal dispatching of the relatives who cruelly damned his beloved mother into poverty for having married his father. As is the case with most successful satires, both films deny us the comfort of a traditional protagonist. This is especially true of Theater of Blood, where the character who would normally be the film’s hero (especially if it had been made in the States) is an arrogant, insufferable prick whose escape from death results in our disappointment rather than any sense of exhilaration.

Another reason I love the film is because it is a classic British satire masquerading as a Vincent Price horror movie—a black comedy where murder is ably played for laughs because of our natural dislike for the victims, especially when compared to their much-more sympathetic executioner. In that way it is a spiritual heir to Robert Hamer’s 1949 Ealing Studio’s masterpiece Kind Hearts and Coronets—in which we eagerly cheer on a charmingly amoral shop clerk whose ascent into the aristocracy is hastened by his lethal dispatching of the relatives who cruelly damned his beloved mother into poverty for having married his father. As is the case with most successful satires, both films deny us the comfort of a traditional protagonist. This is especially true of Theater of Blood, where the character who would normally be the film’s hero (especially if it had been made in the States) is an arrogant, insufferable prick whose escape from death results in our disappointment rather than any sense of exhilaration.Add to that the supremely witty device of having Lionheart dispatch his victims using scenes from The Bard as his inspiration and the always-pleasurable sight of a 60s-era Diana Rigg (who bizarrely spends much of the movie in hilarious male drag, but more than makes up for it for with her more overtly feminine ensembles) and you have what is—to my way of thinking—a perfect cinematic experience.

That said, I can understand how some folks might believe it odd that I would choose to link it with Anderson’s film—even with their similar sounding titles—but the more I think about it, the more the comparison seems apt.

To start off with, both are films about obsession, which is a theme I have always strongly connected with. Looking back it is a motif found in many of the films that most affected me during the course of my life—from The Rapture to All That Jazz to Jaws 4: The Revenge, I’ve always found myself inclined to empathize with obsessive characters, especially when their obsessions err on the wrong-side of self-destruction.

In the case of both Plainview and Lionheart (I love how both character’s last names evoke the essence of their personalities, Plainview’s serving as testimony to his pragmatism, while Lionheart’s gives credence to his self-coronation as the king of all actors) it is their obsessions that lead to their greatest moments of humiliation, which both in turn lead to the spilling of the blood described in both films’ titles.

Unsatisfied with his popular success, Lionheart craves the critical recognition that has eluded him his entire career. After 30 years of performing Shakespeare, he is certain that he has finally produced a season worthy of the Critic’s Circle Award, but the critics disagree and instead award the honor to a young method actor, whose frenetic, inarticulate performance stands in sharp contrast to Lionheart’s classical approach. Unable to accept his defeat, Lionheart confronts the assembled critics after the ceremony, only to realize—too late—that doing so has only made his humiliation at their hands that much more untenable.

Driven not just to succeed, but to also crush all those who would dare compete with him, Plainview finds his plans to build an oil pipeline jeopardized when he discovers that he has no right to build on a crucial parcel of land. When the owner makes it clear that the only way for him to get what he wants is to ask Jesus to forgive his sins (including the murder he has committed just hours earlier) and join the church run by Eli Sunday, a man he loathes, Plainview acquiesces and—for the good of his business—undergoes the humiliation of a staged (and completely spurious) spiritual awakening.

More than anything it is the nature of these two humiliations that causes me to not only identify, but also sympathize with the two men when they are later driven to murder.

My vehemence towards those who make a living criticizing the works of others is not dissimilar to the anti-smoking stridency of a former pack-a-dayer. In my youth my ability to point out the flaws found in others was my only weapon against the various trivial abuses that were thrown my way during that period of my life. Lacking the size to fight, I had no choice but to rely on a withering wit in order to earn a small measure of vengeance against those who would choose to bully me. The problem was that this wit and the cynicism it nurtured created an armor around me that made it impossible for me to connect with the people I came across. For that reason I deliberately rid myself of my instinct to seriously judge the efforts of others, as well as the absurd belief that any such judgments had any worth outside of my own mind. This is why I have so little respect for anyone my age who still harbors the ridiculous notion that their opinions are inherently worth more than others and should be treated as words spoken from on high, rather than their own biased and easily-debatable judgment.

It also certainly helps that, unlike the majority of the men and women who make a living as critic, I have actually faced criticism myself and know firsthand how unpleasant it is to be insulted by someone who clearly isn’t familiar with me or me work (their comments clearly indicating that they haven’t even read the book they’re writing about), but has a column to fill and a superior attitude to feed and nurture.

No wonder then all of my empathy goes toward Lionheart and not the men and woman who took so much sadistic pleasure belittling him over the years—finally driving him to attempted suicide (he survives the fall seen at the end of the above clip). His sadism, as lethal as it is, has long been equaled by their own.

Karma is a bitch.

In the case of Plainview, his humiliation strikes me as even worse than Lionheart’s, although it is mitigated by his willingness to subject himself to it in order to get what he wants. Were he willing to give up his dream of the pipeline, he could spare himself the indignity of self-incrimination and false-epiphany, but it is exactly this determination of his that Eli Sunday exploits in order to avenge the slights Plainview has committed against him in the past.

In a less complex character study, Plainview’s acquiescence would be the clearest signal of his soullessness—his paucity of character and ethics—but in the hands of masters such as Anderson and Daniel Day-Lewis, it is instead the truest example of the pragmatism that defines who he is. With one look, Plainview makes it clear that Sunday will eventually pay for this trespass, even if it takes 16 years for the debt to finally be paid.

But there is more that connects these two characters than their desire to revenge past humiliations. They are both fathers.

More than anything it is the nature of these two humiliations that causes me to not only identify, but also sympathize with the two men when they are later driven to murder.

My vehemence towards those who make a living criticizing the works of others is not dissimilar to the anti-smoking stridency of a former pack-a-dayer. In my youth my ability to point out the flaws found in others was my only weapon against the various trivial abuses that were thrown my way during that period of my life. Lacking the size to fight, I had no choice but to rely on a withering wit in order to earn a small measure of vengeance against those who would choose to bully me. The problem was that this wit and the cynicism it nurtured created an armor around me that made it impossible for me to connect with the people I came across. For that reason I deliberately rid myself of my instinct to seriously judge the efforts of others, as well as the absurd belief that any such judgments had any worth outside of my own mind. This is why I have so little respect for anyone my age who still harbors the ridiculous notion that their opinions are inherently worth more than others and should be treated as words spoken from on high, rather than their own biased and easily-debatable judgment.

It also certainly helps that, unlike the majority of the men and women who make a living as critic, I have actually faced criticism myself and know firsthand how unpleasant it is to be insulted by someone who clearly isn’t familiar with me or me work (their comments clearly indicating that they haven’t even read the book they’re writing about), but has a column to fill and a superior attitude to feed and nurture.

No wonder then all of my empathy goes toward Lionheart and not the men and woman who took so much sadistic pleasure belittling him over the years—finally driving him to attempted suicide (he survives the fall seen at the end of the above clip). His sadism, as lethal as it is, has long been equaled by their own.

Karma is a bitch.

In the case of Plainview, his humiliation strikes me as even worse than Lionheart’s, although it is mitigated by his willingness to subject himself to it in order to get what he wants. Were he willing to give up his dream of the pipeline, he could spare himself the indignity of self-incrimination and false-epiphany, but it is exactly this determination of his that Eli Sunday exploits in order to avenge the slights Plainview has committed against him in the past.

In a less complex character study, Plainview’s acquiescence would be the clearest signal of his soullessness—his paucity of character and ethics—but in the hands of masters such as Anderson and Daniel Day-Lewis, it is instead the truest example of the pragmatism that defines who he is. With one look, Plainview makes it clear that Sunday will eventually pay for this trespass, even if it takes 16 years for the debt to finally be paid.

But there is more that connects these two characters than their desire to revenge past humiliations. They are both fathers.

It could be argued that Plainview’s most monstrous acts are not the two murders he commits or his role in the accidental deaths of the men in his employ, but rather the mistakes he makes in his relationship with his adopted son, H.W.—namely the abandonment with which Eli taunts him during his supposed conversion.

Many reviewers have suggested that Plainview uses the boy as little more than a prop—a helpful tool necessary to sell himself to wary locals as an upstanding family man. Plainview says as much when an adult H.W. informs him that he is leaving to start his own business, but I don’t believe him. In one of the film’s most powerful scene’s Plainview describes himself as a misanthrope who has never had much use for people, but his actions suggests that for all of his contempt for humanity, he himself is never so cut off as to not yearn for the connection that comes from family.

The proof of this is the fact that he only decides to send the newly deaf H.W. away once he has found a surrogate in Harry Brands, his long-lost half-brother. Even after this his repeated concern over the size of H.W’s room at the institution belies his genuine concern and once Brands’ lie is exposed, he immediately brings H.W. back home.

There is no doubt that Plainview is a selfish bastard, whose own needs always outweigh those of the people around him, but I would stop short of describing him as a sociopath. When he lashes out at his adult son, he does so because he himself feels as though he is being abandoned—he is hurt by H.W’s decision to be his own man rather than continue the partnership that began the day he made him his son (and, it should be said, by the far creepier reason that Mary, the little girl he admired just a bit too much, chose to marry H.W. rather than him, although that’s purely speculation on my part and is not explicitly suggested in the film).

Despite his being a bad person, Plainview’s need for family keeps him from being a monster and the same is equally true for Lionheart, whose murderous deeds are somehow made less horrific by the loving involvement of his daughter, Edwina (her name alone serving as testament of his own self-devotion).

Many reviewers have suggested that Plainview uses the boy as little more than a prop—a helpful tool necessary to sell himself to wary locals as an upstanding family man. Plainview says as much when an adult H.W. informs him that he is leaving to start his own business, but I don’t believe him. In one of the film’s most powerful scene’s Plainview describes himself as a misanthrope who has never had much use for people, but his actions suggests that for all of his contempt for humanity, he himself is never so cut off as to not yearn for the connection that comes from family.

The proof of this is the fact that he only decides to send the newly deaf H.W. away once he has found a surrogate in Harry Brands, his long-lost half-brother. Even after this his repeated concern over the size of H.W’s room at the institution belies his genuine concern and once Brands’ lie is exposed, he immediately brings H.W. back home.

There is no doubt that Plainview is a selfish bastard, whose own needs always outweigh those of the people around him, but I would stop short of describing him as a sociopath. When he lashes out at his adult son, he does so because he himself feels as though he is being abandoned—he is hurt by H.W’s decision to be his own man rather than continue the partnership that began the day he made him his son (and, it should be said, by the far creepier reason that Mary, the little girl he admired just a bit too much, chose to marry H.W. rather than him, although that’s purely speculation on my part and is not explicitly suggested in the film).

Despite his being a bad person, Plainview’s need for family keeps him from being a monster and the same is equally true for Lionheart, whose murderous deeds are somehow made less horrific by the loving involvement of his daughter, Edwina (her name alone serving as testament of his own self-devotion).

Edwina is by far the oddest and most complex character in the film, thanks to the brilliant device of having her always appear in male drag virtually every time she assists her father during one of his murders. By giving her two separate personas, the real Edwina remains sympathetic throughout the film, even as she helps her father drown, decapitate and electrocute his various victims. At the end of the film it seems clear that she will go unpunished for her involvement, which provokes relief rather than disappointment from the audience. But beyond her disguise, the other aspect that mitigates her crimes is her obviously love for her insane father.

If Plainview is a monster humanized by his need for family, than Lionheart is a monster humanized by his family’s need for him. His relationship with Edwina is—apart from the abhorrent nature of his victims—the key element that keeps us rooting for him to succeed even as his actions grow more and more horrific.

Wrapping up, I’ll admit that I’m probably the only person on the planet willing to make the connection between these two films. In the end that connection may be built on something as fragile as my own responses to them, but that’s enough to convince me that it’s there and to urge you to see both of these films sooner rather than later.