(Note: I got distracted and wrote something else other than what I promised to deliver today. Please feel free to take your dissatisfaction out of my paycheck.)

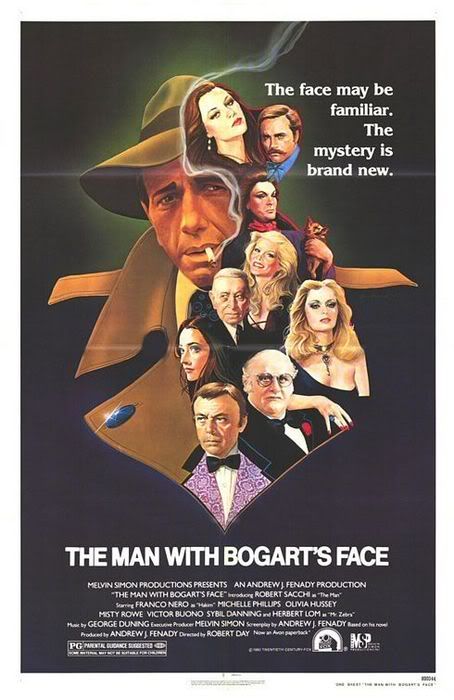

One of the major benefits of my current “day” job (or—more accurately—my “late night/early morning” job) is that it does allow me enough down time to watch movies in-between instances of absorbing drunken abuse from assholes who don’t quite understand how the world works. Last night I treated myself to a cinematic oddity from 1980 called The Man With Bogart’s Face, a comedy starring Humphrey Bogart impersonator Robert Sacchi as Sam Marlowe, a movie-obsessed private detective who undergoes plastic surgery in order to look like his favourite star.

Despite being based on such a potentially flimsy gimmick, the film is actually far more entertaining than it has any right to be. Andrew J. Fenady's script (which is based on his own novel) is filled with genuinely funny one-liners and affectionate references to Hollywood’s Golden Age. Plus, speaking as a movie buff who is more than a little obsessed with Gene Tierney, it’s hard not to like a movie that features a main character who shares that obsession and a leading lady explicitly styled to resemble the famously troubled actress (shockingly, former “Mama” Michele Phillips almost pulls it off with only her lack of an overbite and her thin, stringy hair holding her back).

The film is also elevated by a great supporting cast, including Victor “King Tut” Buono, Franco Nero (as a Turk obsessed with the colour blue), Yvonne De Carlo (who manages to get laughs despite not saying a word in either of her two scenes) and the gorgeous trio of Olivia Hussey, Misty Rowe and Sybil Danning (the last two looking especially amazing in a series of skintight outfits).

In fact the only thing keeping the film from achieving the full-on cult status it probably deserves is the bland, static direction of Robert Day and the over-lit, saturated cinematography of Richard C. Glouner, both of which overshadow the intriguing noir-satire lurking beneath the film’s surface, making The Man With Bogart’s Face look like a well-produced, but uninspired TV movie. Admittedly, it’s a tricky line to walk and Steve Martin and Carl Reiner’s Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid proves that it’s just as easy to err in the other direction, but by playing it too conservatively the filmmakers ended up with a good movie instead of a great one (still, I would choose it over Neil Simon's similar The Cheap Detective any day of the week).

That said, I’m not writing about the film because I want to alert your attention towards it, but rather because while I was watching it I was confronted by a reality of critical engagement that people seldom acknowledge. That reality is the one indicated in the title of this post—knowledge is perception. That is to say, how we perceive something is deeply dependent on how much we know about it beforehand. Now, I recognize this is a stunningly obvious observation, but I find that many people seem unwilling to admit how much irrelevant trivia affects their critical judgment.

Now in some cases people use this trivia merely to justify opinions that would otherwise seem petty or unreasonable. A lot of people already hated Woody Allen for being an icon of certain kind of neurotic, east coast (read: Jewish) personality, but his marrying the much-younger adopted daughter of a woman he had children with gave them what they considered to be a tangible reason for their dislike. By the same token many women were already put off by Angelina Jolie’s exotic sensuality and the supreme confidence she exudes in her roles long before she “stole” Brad Pitt away from the much more relatable (read: safe, boring, non-threatening) Jennifer Aniston. But in this case I’m talking about how a single piece of added knowledge can totally alter your perception of a work towards which you have no previous prejudice.

Near the beginning of The Man With Bogart’s Face, the film’s titular character meets his first client, a very large women who also happens to be his landlord. She needs him to find her lost lover and as a reward has promised him three months free rent.

Watching this scene I became curious about who was playing the part of “Mother”, Marlowe’s Amazonian Landlady. While in a previous lifetime my curiosity would have gone unfilled, that night all I had to do was look up the movie on the IMDb. There I found the brief filmography of an actress named A’lesha Brevard and was slightly startled to discover that despite my never having known her name before, she had in fact been making an appearance on one of my walls for over a year now.

Back in 2007, I watched one of the funniest comedies I had ever seen when I threw in a copy of Nat Hiken’s 1969 social satire The Love God?. In the film, Don Knotts portrayed Abner Peacock, a shy, bookish 30-something virgin (it’s actually an important plot point) whose family-owned bird-watching magazine is saved from bankruptcy when he unwittingly agrees to become the publisher of the Playboy-esque Peacock magazine and is then promoted by its crooked financiers and cynical-yet-sexy editor, Lisa Lamonica (Anne Francis) as a worldly, sophisticated Hugh Hefner figure to serve as the magazine’s figurehead (and eventual fall guy). Like any sophisticated playboy running an adult magazine empire, Abner doesn’t go anywhere without his exotic collection of lady companions, one of whom (the redhead) is played by the future landlady of Sam Marlowe:

I so enjoyed the film that when the opportunity came up to buy a vintage copy of the film’s poster, I jumped at it, but once I bought it, I never thought to look up the names of the women it presented to me. So, having had A’lesha on my wall for a year, I decided to investigate further and checked out the website section of her IMDb page, which led me to a site devoted to “Glamour Girls of the Silver Screen”.

On this page I found a very brief chronological history of her career—one which I soon discovered omitted the one fact that made her story very unique from any other “Glamour Girls” spotlighted on the website. The only clue this page left to what that fact was came when it informed me that in 2001 she “publishe[d] her bestselling autobiography The Women I Was Not Meant To Be at Temple University Press.” At that point I assumed the book’s title referred to how her life diverged dramatically from where it had began and I guessed that after she left the movie business she became a missionary or a doctor or something like that. Since the last bit of information on the page was the url for her own personal website I decided to check it out.

And it was there at Aleshabrevard.com, that I discovered the real meaning of her book’s title. In 1937, A’lesha had been born Alfred Crenshaw and in 1962, at the age of 25 became one of the first Americans to undergo sexual reassignment surgery. A’lesha Brevard was a transgendered woman.

Now I was previously familiar with the story of Caroline Cossey, who as “Tula” caused a minor scandal years ago when it was discovered that her brief appearance in For Your Eyes Only made her the first and only trans “Bond Girl”, but I had no idea that A’lesha had done the same thing a decade earlier. “That’s pretty cool,” I thought to myself as I turned off my browser and went back to watching the movie.

This piece of new trivia didn’t affect my thoughts on the film until near the end when A’lesha returned onscreen to be reunited with her “lost” lover (it turned out he had merely gone into hiding so he could get himself into the physical condition he needed to be in to be “worthy” of her). The first time I saw her in the film, I knew she had a unique presence, but I had concluded this was more due to her size than anything else, but now when she spoke I didn’t hear the voice of a large woman, but that of a man in drag. It completely threw me out of the scene and instead of watching the characters interact I couldn’t help but ponder a host of ultimately irrelevant questions (such us “Did the producers know they had cast a trans performer on purpose or had A’lesha just proved uniquely perfect for the part?”) as it went on.

But simultaneously with this reaction I was able to recognize that the quality of her performance had not changed, I had merely learned something that affected how I perceived it. This struck me as fine, so long as I acknowledged why my perception had changed and regarded it as a fault of my own and not the film’s. The film had not changed—I had.

Back when I was in university I frequently disagreed with my professors over the idea that the production history of a film should have no bearing on our critical appreciation of it and that these “behind the scenes” stories were nothing more than trivia. As a lover of film history who treasured these stories as much, if not more, than the films themselves this approach struck me as extremely arrogant. As a “creative person” I couldn’t help but abhor the popular academic idea that the artist was less important than the viewer who “constructed” the narrative in their mind, if only because it seemed a pathetically obvious way to make the academics the most important people in the process, instead of the boring leaches they so often are.

The truth is, though, is that these same professors frequently did allow this “trivia” to affect their critiques—they simply refused to acknowledge it. Though Anthony Perkins’ homosexuality wasn’t explicitly mentioned by a lecturer, the news of it had clearly affected their read on Norman Bates and so on.

The human brain will always adapt its conclusions when provided with further data; this is an inescapable fact of life. I just wish that more people would take the time to acknowledge this and review how it affects their own judgments. As the Internet allows more and more people to share their opinions with the rest of the world, there should be some obligation to be self-aware enough to recognize where those opinions come from and how much they might have been swayed by possibly irrelevant data.

Anyhoo, here’s another brief clip of Ms. Brevard from when she played Giganta on the infamous TV special Legends of the Superheroes.

Knowledge Is Perception