My lazy-ass reposting of holiday-themed material from last year continues, once again with special added content to make the double dip worthwhile.

For a long time I never understood why the folks who wrote horror movie screenplays were all so determined to make the same stupid mistake. Why did they all insist on populating their works with nasty, unpleasant characters who behaved exactly like the kind of assholes people spend a lifetime trying to otherwise avoid? To my mind, such a creative move is anathema to building suspense or effectively scaring your audience, since in order for people to feel tension over a character’s ultimate fate, they shouldn’t actively root for that character’s painful demise. For a horror movie to be scary you have to actually care about what happens to the characters that live and die within them, which is why it has always amazed me how so many filmmakers insist on filling their movies with the same stupid jackasses over and over again.

In Scary Movies, I briefly discussed the idea that one reason for this bizarre choice being so frequently made is the unconscious understanding that slasher movies (to name the subgenre in which the Asshole Conundrum most frequently occurs) aren’t actually meant to scare their loyal audience, but rather make them feel good about their own choices in life. In these films, the assholes were simply meat for the maniac grinder, with their deaths both serving as proof of the depths of the madman’s cunning, strength and cruelty and of what happens to folks who think only of themselves and their own instant gratification. The deaths of these jerks were cheered on by the audience, but once the maniac focused on the movie’s Final Girl (an archetypal character I’ve discussed on this blog before) the audience’s allegiance shifted away from the killer to the lone character they’ve been allowed to identify with, thus giving the movie’s climax a sense of true urgency. And though this does make good narrative sense and explains why the subgenre has proven so popular over the years, it also illustrates the prime reason most slasher movies aren’t the slightest bit frightening.

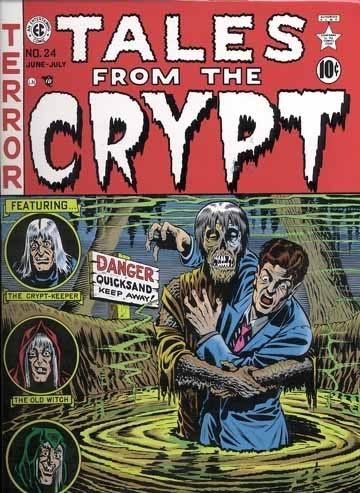

But that’s just one possible reason for the existence of the Asshole Conundrum. Another is one I’ve just recently started thinking about, but that I think makes just as much sense. Much of what we think of as horror in film today didn’t exist for the first 50 years or so of the medium’s history. It really wasn’t until Psycho came out in 1960 that horror movies moved beyond the then traditional sphere of gothic mysteries and/or tales of the supernatural or science run amok, but during the decade before Hitchcock’s movie was released this kind of modern horror did have a popular outlet in the form of comic books. Though many companies produced horror anthologies throughout the 50s--before they were effectively banned following the creation of the Comic Code Authority--easily the best and most famous of these were the ones published by William Gaines’ Entertaining Comics (formally Educational Comics, but best known to everyone as EC Comics for short).

EC’s horror comics were far more inspired by the world of film noir than they were by the more traditional Universal horror movies. Even though the stories in their books all featured typical monsters like vampires, werewolves, witches and zombies, it was far more likely that you would come across a character that more closely resembled Richard Widmark in Kiss of Death (who famously laughed as he pushed an old women in a wheelchair down a flight of stairs) than Bela Lugosi's Dracula or Boris Karloff'sFrankenstein. As its name suggests film noir was a dark genre whose depiction of reality matched the shadowed filled grayness of its distinct cinematography. It was a world where the line between the hero and the villain was so fine even they would have trouble distinguishing it. EC took this idea and stretched it to its furthest limits—to the point that many of its stories could much more easily read as darkly comic morality tales than simple horror yarns.

EC’s horror comics were far more inspired by the world of film noir than they were by the more traditional Universal horror movies. Even though the stories in their books all featured typical monsters like vampires, werewolves, witches and zombies, it was far more likely that you would come across a character that more closely resembled Richard Widmark in Kiss of Death (who famously laughed as he pushed an old women in a wheelchair down a flight of stairs) than Bela Lugosi's Dracula or Boris Karloff'sFrankenstein. As its name suggests film noir was a dark genre whose depiction of reality matched the shadowed filled grayness of its distinct cinematography. It was a world where the line between the hero and the villain was so fine even they would have trouble distinguishing it. EC took this idea and stretched it to its furthest limits—to the point that many of its stories could much more easily read as darkly comic morality tales than simple horror yarns.

Given how popular and influential these comics were during their brief existence, it really isn’t surprising that the kids who read them and went on to become screenwriters assumed that populating a horror tale with unlikable characters was not only important, but de rigueur for the genre to properly work. What they failed to realize was that the stories they found so frightening as children would more likely illicit a chuckle from them now that they were adults. Not because the stories were inept, but rather because at their best they were masterpieces of ironic comeuppance in which a kind of universal justice ensured that the fate of evil folks was ALWAYS far worse than that experienced by their victims. Unforunately many of these EC-inspired screenwriters kept the unlikeable characters they remembered from their youth, but left out the irony that made the inclusion of such characters worthwhile. Perhaps if their memories were a little sharper, they might have recalled that the scariest of the EC tales were the rare ones in which the nice, innocent person suffered the most.

Now this very long introduction leads me to #4 in my countdown of the top five moments in cinematic Christmas holiday horror. Originally published in EC comic’s The Vault of Horror, “And All Through the House” proved so memorable it has actually been filmed twice, once in 1972 and again in 1989. The first version appeared in a British movie produced by Amicus Productions called Tales From the Crypt. As its name implies, the film was an anthology of stories culled from EC comics and it starred a very embarrassed looking Sir Ralph Richardson as the Crypt Keeper, whose duty it is to explain to the confused folks brought before him how they had ended up in his lifeless domain. The second version was (not surprisingly) produced for HBO’s Tales From the Crypt TV series, where it appeared in the show’s first season. Like all of the six shows produced that first year, it was directed by one of its famous co-producers, in this case future Oscar winner Robert Zemeckis.

Of the two versions, I think I kinda like the first one best. Although both versions are extremely faithful to the plot of the original story, they vary greatly in their tone. Freddie Francis’ 1972 version features Joan Collins in the main role of the murderous/victimized housewife and it eschews the story’s more farcical comic aspects for a jolt of pure terror. Amazingly Collins manages to remain sympathetic throughout the short film, even though the first thing we see her do is kill her husband so that she can share his fortune with her unnamed lover. By contrast, Zemeckis’ 1989 version, which stars his then-wife Mary Ellen Trainor, is a much more comic piece that is (I’m guessing) actually closer in spirit to the comic book. But rather than serving as its greatest strength, this fidelity to the comic is precisely why it fails to be as unnerving as the 1972 version—it simply isn’t scary. While I do appreciate humour in my horror, it should never come at the expense of the film’s true purpose, which is why—in this case—I prefer the more serious adaptation.

Of the two versions, I think I kinda like the first one best. Although both versions are extremely faithful to the plot of the original story, they vary greatly in their tone. Freddie Francis’ 1972 version features Joan Collins in the main role of the murderous/victimized housewife and it eschews the story’s more farcical comic aspects for a jolt of pure terror. Amazingly Collins manages to remain sympathetic throughout the short film, even though the first thing we see her do is kill her husband so that she can share his fortune with her unnamed lover. By contrast, Zemeckis’ 1989 version, which stars his then-wife Mary Ellen Trainor, is a much more comic piece that is (I’m guessing) actually closer in spirit to the comic book. But rather than serving as its greatest strength, this fidelity to the comic is precisely why it fails to be as unnerving as the 1972 version—it simply isn’t scary. While I do appreciate humour in my horror, it should never come at the expense of the film’s true purpose, which is why—in this case—I prefer the more serious adaptation. But….

The 1972 version isn’t yet available on DVD, while the 1989 adaptation can be found on the Tales From the Crypt first season box set, so I am forced to present the #4 moment in my countdown using images (and basic plot description, since it has been years since I saw the 1972 film and there may be minor differences I don't remember) from what I have just argued is the inferior version of the story. So it goes….

WARNING!

I am about to completely give away the story’s ending, since that’s when the memorable moment occurs. Just so you know, this will also happen with moments #3 and #1.

Our story begins in a nice quiet home on Christmas Eve. Having put her impatiently-waiting-for-Santa daughter to bed, an angry wife (named Joanne Clayton in the 1972 film, but left unmonikered in the 1989 version) grabs a a poker from beside the fireplace and uses it to kill her husband. Thrilled by what she has done she calls her lover and informs him that they are now free to be together and spend her murdered husband's fortune any way they please. But before the celebration can really begin, she has to perform the unpleasant chore of getting the body out of the house and make it look as though her late husband's death was an accident. As she goes to work, a bulletin goes out over the radio informing the public that a madman has escaped from a local mental institution and brutally murdered four women with an ax. The radio announcer goes on to describe the maniac, adding that he is apparently dressed in a Santa Claus costume he stole from one of his victims. She is too busy to hear this, but learns about it anyway when the psychopath in the Santa suit comes from out of nowhere and attacks her just outside her house. Fortunately she is able to get away from him and run inside, where she picks up the phone to call for help--only to realize that Santa isn't the only murderer in the vicnity that the police are going to be interested in.

unmonikered in the 1989 version) grabs a a poker from beside the fireplace and uses it to kill her husband. Thrilled by what she has done she calls her lover and informs him that they are now free to be together and spend her murdered husband's fortune any way they please. But before the celebration can really begin, she has to perform the unpleasant chore of getting the body out of the house and make it look as though her late husband's death was an accident. As she goes to work, a bulletin goes out over the radio informing the public that a madman has escaped from a local mental institution and brutally murdered four women with an ax. The radio announcer goes on to describe the maniac, adding that he is apparently dressed in a Santa Claus costume he stole from one of his victims. She is too busy to hear this, but learns about it anyway when the psychopath in the Santa suit comes from out of nowhere and attacks her just outside her house. Fortunately she is able to get away from him and run inside, where she picks up the phone to call for help--only to realize that Santa isn't the only murderer in the vicnity that the police are going to be interested in.

unmonikered in the 1989 version) grabs a a poker from beside the fireplace and uses it to kill her husband. Thrilled by what she has done she calls her lover and informs him that they are now free to be together and spend her murdered husband's fortune any way they please. But before the celebration can really begin, she has to perform the unpleasant chore of getting the body out of the house and make it look as though her late husband's death was an accident. As she goes to work, a bulletin goes out over the radio informing the public that a madman has escaped from a local mental institution and brutally murdered four women with an ax. The radio announcer goes on to describe the maniac, adding that he is apparently dressed in a Santa Claus costume he stole from one of his victims. She is too busy to hear this, but learns about it anyway when the psychopath in the Santa suit comes from out of nowhere and attacks her just outside her house. Fortunately she is able to get away from him and run inside, where she picks up the phone to call for help--only to realize that Santa isn't the only murderer in the vicnity that the police are going to be interested in.

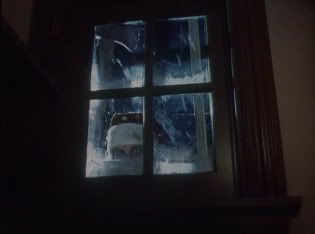

unmonikered in the 1989 version) grabs a a poker from beside the fireplace and uses it to kill her husband. Thrilled by what she has done she calls her lover and informs him that they are now free to be together and spend her murdered husband's fortune any way they please. But before the celebration can really begin, she has to perform the unpleasant chore of getting the body out of the house and make it look as though her late husband's death was an accident. As she goes to work, a bulletin goes out over the radio informing the public that a madman has escaped from a local mental institution and brutally murdered four women with an ax. The radio announcer goes on to describe the maniac, adding that he is apparently dressed in a Santa Claus costume he stole from one of his victims. She is too busy to hear this, but learns about it anyway when the psychopath in the Santa suit comes from out of nowhere and attacks her just outside her house. Fortunately she is able to get away from him and run inside, where she picks up the phone to call for help--only to realize that Santa isn't the only murderer in the vicnity that the police are going to be interested in. But as the two of them engage in a terrible game of cat and mouse, she realizes that if she can keep the maniac at bay long enough for the police to arrive, she could convincingly pin the murder of her husband on him and kill two birds with one stone. Having knocked the sick Santa unconscious, she proceeds to use his ax on her husband's body (this is a part I don't think was included in the 1972 version, but I could be wrong about that) and then runs back inside the house and calls the police, informing them that she's being attacked by the escaped lunatic and that he has already killed her husband. The emergency operator tells her to stay on the line and find a weapon. Following this advice, she runs to a closet in search of her husband's gun, but she can't quite reach it and inadverdently locks herself in the closet (again, I don't remember this happening to Joan Collins, but it might have). There she is horrified to discover that the insane ax murderer has found a ladder and is climbing up towards the open window in her daughter's room.

Making the situation worse than it already is, the woman's daughter (Carol in 1972, Carrie Ann in 1989) wakes up and completely fails to recognize the man climbing towards her window as a dangerous threat and instead assumes he is the real Santa Claus coming to deliver her presents. Thrilled to see him, she urges him to climb faster as her mother watches in horror.

But it would seem that luck is on the women's side, since the ladder is too short to reach the open window and she is finally able to escape from the inside of the closet. Terrified, she runs to her daughter's room and finds that it's empty. Screaming her daughter's name she runs downstairs only to find her safe and sound at the bottom of the stairs.

However this is a tale of holiday horror, so all is not as it seems and memorable moment #4 has to occur.

"See, Mommy," the little girl says excitedly, "I told you Santa would come and he didn't even have to come down the chimney!"

Wait for it....

"I let him in!"

"Naughty or nice?" asks the maniac as his next victim begins to scream.

And that's the ballgame.

Interestingly, in the Crypt Keeper's wrap up of the episode, they have him specifically mention that the little girl survived the encounter with the ax-murderer, explaining that "Our particular Santa prefers older women. In pieces, that is!" I find it funny that even a horror anthology series on taboo-breaking HBO would find it necessary to spare their viewers the thought of a murdered child. However, I'm twisted enough to conclude that after watching her mother being cut into pieces by Santa, the girl was sent to the same orphanage Billy Chapman once went to and it's only a matter of time before she snaps Silent Night, Deadly Night style and the holiday horror fun begins anew.

Updated Content!

Ten months after I originally wrote this post, the good people at 20th Century Fox saw fit to release the original 1972 Tales From the Crypt as part of its Midnight Madness DVD series. Thankfully they also had the good sense to package it along with Amicus' second E.C. comics adaptation Vault of Horror (which was actually released in some places as Tales From the Crypt II) and I had the equally good sense to purchase it the first moment I saw it. Thus I am now able to report with 100% confidence that the Joan Collins' version of the tale I described above is indeed as superior as I remembered it, but rather than describe it in my usual boring detail, I'll just list the reasons why it's better than the Zemeckis version and then ignore all decent copyright laws by embedding the sequence in its entirety, so you can enjoy it for yourselves.

Ten Reasons Amicus' Version is Better Than HBO's

1. In her twenties Joan Collins was widely regarded by many as one of the most beautiful women in the world, possibly second only to Elizabeth Taylor at her prime. At 39 she was still unreasonably attractive, so much so that one wishes there was a short crude acronym for sexually alluring women of a certain age with which to describe her. Without one coming to mind, I shall say that she was a Mature Woman I'd Sex Proper or a M.W.I.S.P. for short (consider that term officially coined and a registered trademark of this blog). And while I'm certain Mary Ellen Trainor is a very nice person, it's pretty obvious that she only got the gig because she was sleeping with the director at the time.2. As directed by famed cinematographer Freddie Francis, the Amicus version includes at least one moment that genuinely made me jump in my seat. Zemeckis' version kept my butt firmly planted on the couch the entire time.3. The simple dirty face and fake beard of the Amicus maniac is far creepier than the more elaborate "crazy-ugly-guy" make-up used in the remake. 4. Having just very recently suffered through the truly terrible Dr. Giggles, I am now unreasonably prejudiced against any work featuring Larry Drake. And yes there will be a DVD Index in the future to justify this sudden hostility towards the man who once played everyone's second-favourite television retard.5. I like that in the Amicus version the murdered husband is portrayed as a loving man who is completely unaware that he's married to a psychopathic bitch right up until the moment she brains him with a fireplace poker, while the HBO version attempts to make its protagonist's crime seem more reasonable by making the husband a rude, abusive jerk, who therefore had it coming to him.6. Everything is better when it has English accents in it.

4. Having just very recently suffered through the truly terrible Dr. Giggles, I am now unreasonably prejudiced against any work featuring Larry Drake. And yes there will be a DVD Index in the future to justify this sudden hostility towards the man who once played everyone's second-favourite television retard.5. I like that in the Amicus version the murdered husband is portrayed as a loving man who is completely unaware that he's married to a psychopathic bitch right up until the moment she brains him with a fireplace poker, while the HBO version attempts to make its protagonist's crime seem more reasonable by making the husband a rude, abusive jerk, who therefore had it coming to him.6. Everything is better when it has English accents in it.

7. Did I mention that Joan Collins is really, really hot? I did? Well, it's true and I don't mind repeating it. She's a total M.W.I.S.P.TM!

8. At just barely over 12 minutes in length, the Amicus version is all killer and no filler.9. No lame Crypt Keeper puns.10. I have no reason to believe this beyond a simple gut feeling, but I'm fairly certain that the young actress who played the daughter in the original version grew up to become a very sweet woman, while the one in the remake grew up to become the type of person who enjoys poisoning neighbourhood pets. Again, I can't prove this, but I'm 85% certain that it's true. Part One

Part One

Part Two