Before I begin my long overdue penultimate installment in my look at my Ten Favourite Cinematic Devils, I have what may or may not be good news depending on your overall appreciation of this lil’ ole blog o’mine. Right at this moment, from what I am certain is one of China’s cleanest and most productive factories, a package containing a shiny new aluminum 4.5 KG, 2.4 Ghz, Intel Core 2 Duo, 2GB DDR3 Memory, 250GB hard drive MacBook is on its way to my doorstep and about to usher in a brand new era in my productivity.

Y’see, my main obstacle in keeping the H of G updated as much as I would have liked was the fact that for 40 hours a week I have been kept away from a decent computer with unfettered access to the Internet. Even though the nature of my job allows for ample wastage of time in whatever manner I desire, the simple lack of technology kept me from doing anything other than watching DVDs on my portable player, reading the occasional book or playing Monopoly/Scrabble on my iPod.

Obviously that paradigm has shifted.

Now I don’t want to raise any false expectations and suggest this augers a return to my once-a-day habits of old. My focus is still going to be on the creation of long, self-indulgent posts on matters only I care about—I’m simply going to be able to work on them outside of the three or so odd days I have to procrastinate with each week.

You have been warned.

Number Four

Speaking of technology, I tried about a dozen different ways to grab the two relevant scenes from the fourth entry on my list, but for whatever reason the good folks at Criterion decided to get all tricky with their encoding and made it impossible for me to get them off the disk and onto photobucket for your enjoyment. In a way this may be a blessing, since had I posted the two scenes I attempted to copy I would have documented the performance I enjoy so much in its entirety, giving you all the excuse to avoid watching the rest of the film they so nicely bookend. Hopefully the lack of clippage, combined with my skills at rhetoric will convince you to seek out the film and watch the whole thing from beginning to end—a process I guarantee you will all enjoy and thank me for.I am, of course, talking about:

For a movie that makes me so happy there is an awful lot of sadness lurking underneath Lubitsch’s last truly great film, which was his immediate follow up to his masterpiece, the utterly sublime To Be Or Not To Be. Four years after it was completed the master of light-yet-subversive comedy died of a heart attack at the age of 55. Five years later its incandescently beautiful co-star, Gene Tierney, would—as a result of contracting German measles after attending a USO function—give birth to a girl with severe physical and mental handicaps, which directly led to her having a complete mental breakdown. And, perhaps saddest of all, there was the poor fate of the man who played the most courtly and charming version of the Devil ever filmed.

Laird Cregar was an imposing figure who before appearing in Heaven Can Wait had made his greatest impact playing the famous pirate Captain Harry Morgan in the 1942 smash Tyrone Power swashbuckler, The Black Swan. Standing 6’3” and weighing 300lbs, Cregar filled the frame in a way few of his contemporaries could ever hope to match. Only 27 when he appeared as “His Excellency” (this being the amusing title bestowed upon his character in an era where the Hays Office would not allow the name “Satan” to pass through any character’s lips), Cregar easily has the bearing and manner of a man twice his age. But rather than accept his unique physical presence, the young actor saw it as a hindrance to his ambitions. Tired of playing villains like Morgan, the Devil and Jack the Ripper (as he so memorably did in the 1944 remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1927 silent classic, The Lodger) Cregar decided the key to his earning the romantic leading roles he coveted was to go on a massive crash diet and shed the weight that made him appear so fearsome onscreen. In short order he lost over 100 lbs, but he did so with such recklessness his body could not handle the strain and he died from heart failure at the age of 28.

Knowing this can make watching Heaven Can Wait a truly melancholic experience, but at least when watching Tierney’s scenes you can remind yourself that before her breakdown she would truly make her mark with a series of extraordinary performances (including those found in Laura, Leaver Her to Heaven and—my favourite—The Ghost and Mrs. Muir), while watching Cregar only leaves you with a sense of heartbreaking what-might-have-been.

As big as his presence is in the film, Cregar actually only appears in two scenes, at the beginning and end of the film. In it he plays the shockingly polite and courteous ruler of Hell, which in this film is presented more as an unusual bureaucratic post than a position meant to be held by the advocate of all things evil. Sitting at his desk he is greeted by a kindly gray-haired gentleman named Henry Van Cleve (the film’s lead, Don Ameche, in a perfect performance). Van Cleve explains to “His Excellency” that he has come to him because he is certain that the life he has led precludes his entrance, “Up there.”

At first “His Excellency” seems dubious and explains to the elderly gentleman that he will have to go through his file before making a decision—that is to say he gives him the brush off. But then their meeting is interrupted by a woman of Henry’s acquaintance who truly does deserve to go to Hell (despite her protests to the contrary) and is quickly dispatched there via the trapdoor in front of “His Excellency’s” desk. His interest now piqued by the wicked woman’s recognition of Van Cleve, “His Excellency” decides he does in fact have the time to sit down and listen to Van Cleve’s justification for his belief that he is meant to spend the rest of eternity in his domain.

Van Cleve begins his story with his birth and ends it at his death. In all the parts in-between he presents himself as an inveterate and inconsiderate womanizer and scoundrel, but for all of his shameful deeds one can see that his true nature is belied by his love for Martha Strable (Tierney), the daughter of a Kansas millionaire responsible for the majority of the beef eaten in America. After stealing her away from his goody two-shoes cousin Randolph, his relationship with her isn’t without its troubles but its very existence proves that his belief he is destined for damnation is completely unfounded.

When Van Cleve reaches the end of his tale he stands and says, “Your Excellency, that is the story of my life and I’ll be grateful if you push the button and have it over with.”

“No,” the Devil answers him. “Definitely no. I hope you will not consider me inhospitable if I say ‘Sorry Mr, Van Cleve, but we don’t cater to your class of people here. Please make your reservation somewhere else.’”

At first Henry protests, insisting that the people “Above” wouldn’t even let him register, much less check in, but “His Excellency” does not buy it. He admits that Henry might have to spend a few centuries in an uncomfortable room in the annex, but that he is certain there are more than enough residents inside the main building to give him the references he needs. “And if they all should fail, there is still someone else,” he continues.

“Yes,” says Henry. “She’s up there.”

“And she will plead for you,” the Devil tells him.

“Do you think so?”

“You know she will.”

With that “His Excellency” walks his guest to his own private elevator. “Down?” asks the operator. “No,” the Devil smiles and points Heavenward, “up.”

I am not afraid to admit that this sequence pretty much reduces me to tears every time I watch it. As good as Ameche is, though, the blame for this falls squarely on Cregar’s enormous shoulders.

Sigh.

What could have been….

Number Three

As much as success, failure can be an excellent way to determine an artist’s genius. The temptation when looking over a creative person’s legacy is to focus on the good and ignore the bad—the fear being that by acknowledging their failures you risk lessening the impact of their greatest achievements. Having read many biographies over the years I have found you can easily determine how the writer feels about the specific work of their subject by how much ink they decide to devote to it. Several chapters may be devoted to their greatest success, while a much less popular failure can easily be dismissed in a single paragraph or sentence. Personally I find this extremely frustrating as tales of failure are often far more interesting than those of success, but until I start writing all of the books published about artists this isn’t likely to change.

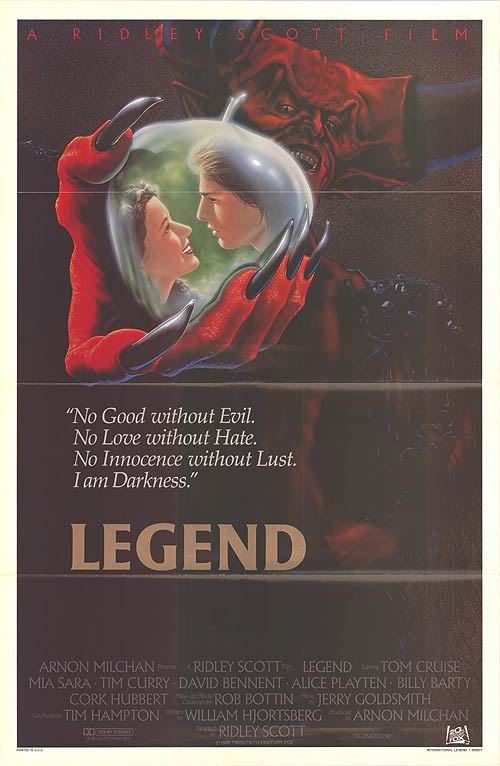

When it comes to Ridley Scott I can assume that most biographers would approach his early work like this: a short chapter on first film, The Duellists (a critical success), a much longer chapter on his second, Alien (both a critical and popular hit), three very-long chapters on his third movie, Blade Runner (an initial critical and financial flop that has since gone on to become one of the most respected movies of all time), and a couple of dismissive sentences on his fourth project, which failed so spectacularly hardly anyone outside of a small cult seems willing to admit it exists.I am, of course, talking about:

And this is the part where you expect me to explain why Legend is an unfairly maligned masterpiece and stands as the most misunderstood film in Scott’s filmography.Not gonna happen.

For all of its merits (it remains, in my opinion, the most visually impressive fantasy epic in the history of the genre, even post-LOTR), Legend must be counted as a failure simply because it isn’t very good. The blame for this lying squarely on the shoulders of screenwriter William Hjortsberg, whose script amounts to nothing more than a series of trite clichés enacted by shallow, one dimensional characters. It didn’t help that the original cut of the film (the one released to theaters and long considered the official version until the director’s cut was released on DVD several years ago) was truncated by its panicked studio to the point of narrative incoherence and further addled by an inappropriate score courtesy of those crazy German synth-meisters Tangerine Dream. That said the longer, Jerry Goldsmith composed director’s cut only proves that all of Scott’s enormous effort was in aid of a project destined to serve as the first unfortunate footnote in his otherwise illustrious career (see also 1492: Conquest of Paradise and Kingdom of Heaven).Why then am I discussing it here?

Because anyone who has actually seen Legend (and we are a rare group indeed) knows that as bad as it may be, it does contain the most singularly amazing representation of a Satanic figure in the history of the medium. And for this the credit goes not to Scott, but rather to makeup artist and special effects guru Rob Bottin, who in crafting the likeness of Darkness (Tim Curry) created one of the most memorable and iconic cinematic images of all time.

A perfect example of style triumphing against content, the best way to illustrate how powerful Bottin’s creation was is simply to show it to you without further comment.