As surprising at it may sound, there was a period in my life where I harbored hopes of one day becoming an actor. Forgoing sports, my extracurricular of choice was drama and it was a field where I—if you’ll forgive my immodesty—did manage to excel. Despite the fact that my preferred style of performance was the “anti-method” (I would take a character and meticulously do everything I could until they resembled myself), I had the strange ability to be far more charming and charismatic on stage than I’ve ever been able to manage in real life. During my school years I won half-a-dozen (that is to say, six) awards and scholarships and imagined myself spending my future as a pint-sized Branagh—directing myself in the theater’s greatest roles.

But then I hit university and was peppered by a series of tiny epiphanies that made me abandon my thespian ambitions. The first was the one I mentioned above—I never so much “acted” as I did present a really entertaining version of myself in front of an audience. The reason for this was explained by my second epiphany—I had no patience at all for the little preparations we were taught were de rigueur before any performance, believing that pure adrenalin was all one needed to get to the final curtain. I had no interest in the craft part of acting—I just wanted to do it. I was like an over-enthusiastic first-time skydiver who blithely ignores the warnings of his instructor because I just wanted to jump out of the plane already. But as addictive as the rush was, the fear I felt before each performance only grew as I continued, rather than abated with experience. What had once only been a nervous tingle before opening curtain was now full blown nausea.

Then there was the realization that even if I did overcome my growing stage fright, truly mastered the craft and became one of the great actors of my generation, my size and appearance would doom me to a lifetime of playing the hero’s comedic best friend. And while it was true those were usually the most fun parts to play, a lifetime spent as a second banana didn’t really appeal to me.

But the fourth and final epiphany was easily the most dramatic—it turned out I didn’t really like live theater and for all of the reasons everyone else seemed to love it. I hated that it was so ephemeral and temporary, especially compared to the immortality of cinema. I hated its artificiality, which I felt robbed it of its power to be truly transcendent and moving. With a movie I could be fooled into believing what I was seeing was really happening, but with theater I was always aware I was watching people play-acting on a stage.

And the egos! Holy crap! The egos!

In terms of sheer undeserved arrogance, the members of no other profession are more deluded in their sense of self-importance than theater people, who in my experience possess a “we-are-changing-the-world” attitude that would be excruciating coming from people who are actually changing the world much less those whose grand achievement consists of decrying man’s inhumanity to man in front of an audience of eight people. (A former roommate—then getting his Masters in Theater Criticism—once told me in all seriousness that a joke I had made months earlier about needing to leave the toilet seat down for our fellow female inhabitant was an example of, “everything we”—we presumably meaning the entire theater criticism community—“are fighting against!”)

The incident that finally allowed me to give up my theatrical dreams without any regrets came when a friend requested that I write her a monologue for an event being held to honor the opening of the university’s new theater. Rather than create one out of whole cloth, I reworked one I had written in high school and was amazed to discover that I got just as much of a rush watching her get a response from material I had written as I had performing the material myself. From that point on, writing became my sole focus.

That’s not to say I regret my brief flirtation with the dramatic arts. In fact I would say that anyone who wants to seriously pursue writing as a profession should take the time to enroll in at least one acting class, as it is easily the best way to develop the empathy required to properly understand a character whose tastes and actions are antithetical to your own. The experience also comes in handy whenever I’m asked to read from one of my books and I have been told by many people who were at my brother’s wedding that mine is the only Best Man speech they have seen awarded with a standing ovation (no, seriously, I kicked ass that night).

And by now I suppose you’re wondering what this has to do with my second post about my 10 favourite cinematic representations of the Devil. Well, it’s simple. Of all the films to feature Satan in all his glory, this is the only one where—had I been the right age and in the right place—I could have played the part.

I am, of course, talking about:

Brian De Palma has always had a difficult relationship with comedy. His early films like Greetings and Hi Mom aren’t so much funny as they are discomfiting (the “Be Black Baby” sequence in the second film being one of the most disturbing examples of social satire I’ve ever seen) and his first Hollywood feature, Get to Know Your Rabbit with Tommy Smothers, was an out and out flop. He completely failed to grasp the point of Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities and the less said about Wiseguys the better.

But none of this applies to Phantom of the Paradise, a rock and roll musical-tragicomedy that marries equal parts of Leroux and Goethe (with a little bit of Wilde thrown in for good measure). To my tastes it’s his most perfect film—filled as it is with all of the cinematic magic tricks that define his style, hilarious performances from an excellent cast and the greatest musical score of its kind. For that last part we can thank Paul Williams, a performer whose contribution to culture has largely been forgotten due to changing tastes in music and his own descent into drug-fueled oblivion, but who was responsible for many of the moments that made the Me Decade worthwhile.

You know that song by The Carpenters that you tell everyone you hate, but that you secretly sing along to whenever you hear it on the radio?

Paul Williams wrote it.

You know that song sung by the green velvet frog that instantly transports you back to your childhood with feelings of melancholic nostalgia?

Paul Williams wrote it.

You know that horrible theme song from that stupid TV show you’ll be able to sing in its entirety until the day you die?

Paul Williams wrote it.

But it is not Paul Williams the musician I want to write about, but rather Paul Williams the actor. As an actor Williams belongs in a select group that features Danny DeVito, Joe Pesci and Prince.

The really short motherfuckers.

Now, as a rule, actors are seldom very tall. Examples like John Wayne, Vince Vaughn and Shaquille O’Neal are the exception rather than the rule. Most are like Tom Cruise, Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino, standing in that nebulous range that can be either 5’4” to 5’9” depending on the kind of shoes they’re wearing. But as short as most male actors are, few successful ones are truly diminutive. At a certain point you can only fool the camera so much and no matter how many apple crates you stand on or how deep a ditch your co-stars stand in, if you’re 5’2” or shorter it’s going to show, usually to the amusement of the audience (what was the whole point of Twins, for example, but to highlight how absurd DeVito looked standing next to his 6’2” Austrian co-star).

It was this cold hard fact of life that helped lead me away from acting, so whenever I watch a film like Phantom of the Paradise where a short actor is allowed to play a major role without his size ever being mentioned, I cannot help but appreciate it purely on a level of “Hey, I could have done that!”

It doesn’t hurt that were you to throw a blond shag wig on my head, I could probably fool most people into thinking Williams and I were related.

The film is about a hapless songwriter named Winslow (William Finley, a truly great seventies character actor who disappeared from film for decades until a small recent role in De Palma’s The Black Dhalia) who earns money playing piano for a mock-greaser singing group called The Juicy Fruits while he composes his meisterwerk—a cantata based on Goethe’s Faust. The Juicy Fruits are managed by Swan (Williams), the most powerful man in the music industry, who overhears Winslow singing one of the songs from his cantata after a performance by his #1 band. Swan decides it’s the perfect sound for the opening of his new rock and roll palace, The Paradise, and instructs his chief henchman, Philbin (George Memmoli) to acquire it for him. Philbin approaches Winslow with the news that Swan wants his music, but the pianist flies into a rage when he is told it will be given to The Juicy Fruits—who he despises—to perform. Despite his misgivings, Winslow hands over his music to Philbin, only to have a month pass without hearing a word from anyone about it. After all his attempts to contact Swan through official channels fail, he shows up at the mogul’s mansion to find that hundreds of young women are practicing one of his songs for a cattle call audition.

One of these singers is the beautiful Phoenix (Jessica Harper) who Winslow helps and falls in love with. Both, however, fail to get what they want. Phoenix leaves when she discovers that in this case “audition” is a synonym for “fuck,” while Winslow is beaten up and thrown out of the mansion when his ruse to masquerade as a member of Swan’s harem fails to impress the mogul. Out on the lawn, the seriously injured songwriter is found by two cops in Swan’s employ who promptly frame him for drug possession, for which he gets a life sentence from an especially harsh judge.

Sent to Sing Sing, Winslow is forced to take part in a medical experiment in which all of his teeth are removed and replaced with metal dentures. Six months later he hears the news of The Juicy Fruits opening the Paradise with “Swan’s Faust” on a guard’s transistor radio and is driven mad enough to escape from the prison in order to stop the opening and get his revenge on Swan. After failing to find Swan at his record label, Winslow goes to the record plant where the new album is being pressed. There he has an accident with a pressing machine that leaves him permanently disfigured.

At the backstage of the Paradise he finds a costume to hide away his disfigurement and listens as a band who looks a lot like The Juicy Fruits, but are now called The Beach Bums, performs an ode to automobiles called “Upholstery” that sounds a lot like the song from his cantata we heard him sing earlier. He plants and detonates a bomb in the prop car, which manages to get Swan’s attention. When Winslow confronts the man who has taken everything away from him, Swan greets him with amused contempt rather than fear. He promises the songwriter—whose vocal chords were damaged in the record plant accident—the ability to sing again and the chance to finish and premiere his cantata in the world’s most important venue. Wary, Winslow is convinced when at an audition for female backup singers he sees Phoenix, whose performance inspires him to finish the cantata so she can become the star he believes her to be. With a little help from technology, Swan makes good on his promise to return Winslow’s voice, although he now sounds a lot more like the record mogul when he sings than he does the piano player we heard earlier. In order to seal their arrangement, Swan insists that Winslow sign a little document—in his own blood. Such are the ways of the record business.

Because he, “abhors perfection in anyone but [him]self,” Swan breaks his promise to give the lead role to Phoenix and instead auditions singers from all sorts of different musical backgrounds. In the end he settles on a coked out glam rocker named Beef (Gerrit Graham), whose exaggerated snarl disguises just another show business queen. When Winslow finds out about this, he isn’t pleased and manages to escape from his music studio, despite the fact that Swan attempted to permanently brick him inside of it. Freed, he confronts Beef and gives him a dire warning:

Beef understandably attempts to flee the theater, but he is stopped along the way by Philbin:

During the performance, Winslow delivers on his warning to Beef and electrocutes him onstage at the end of his song “Life at Last”. This drives the audience wild and the only thing Swan can do to calm them down is to send out Phoenix, whose performance of “Old Souls” manages to both stop a riot and make her an instant star.

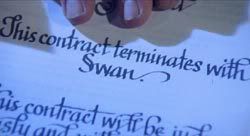

After the show, Winslow lures Phoenix onto the roof of the theater and tries to warn her that the audience has now tasted blood and will demand more from her than she will ever be able to give them. She refuses to believe him and returns to Swan, who takes him back to his mansion. There she does what she wouldn’t the first time she tried to audition for him, while Winslow watches in despair from a skylight in the roof. Unable to take anymore, Winslow stabs himself, but rather than die, Swan arrives and shows him the contract signed between the two of them. He points out that the document explicitly states that. “This contract terminates with Swan,” meaning Winslow cannot die until Swan dies. The stricken songwriter attempts to expedite the process by stabbing Swan, but he does little more than grimace. “I’m under contract, too,” he explains, although he does not say to whom.

It takes little time for Winslow to find out, though. The night of Faust’s big finale, which is set to air on network television and climax with Phoenix marrying Swan and then being assassinated by a sniper hired by the mogul to give the show the most exciting ending possible, the songwriter discovers Swan’s secret video room. In it he finds the recording that serves as Swan’s contract with the Devil himself:

Winslow destroys the recording, causing Swan to rapidly age and burn under his mask (which he wears since his deal with the Devil doesn’t allow him to be photographed by anyone other than himself). He then races to stop the sniper and manages to grab the gun just in time to divert the shot away from Phoenix into Philbin’s forehead. The audience begins to riot, assuming this all part of the show. Phoenix removes Swan’s mask and sees his true face, while Winslow attempts to get to the stage. But as he makes his way, his self-inflicted wound from the roof reopens. Swan is dying, which means their contract has expired and is no longer able to keep him alive. He crawls towards a terrified Phoenix, but it is only after he dies that she realizes what has happened and holds his body as the crowd around her celebrates having seen the greatest rock and roll show of all time.

Phantom of the Paradise is not a film that begs to undergo any kind of deconstruction. It simply is what it is—a vibrant, entertaining horror-comedy show business musical satire. The fact that it features as its villain a 5’2” actor best remembered for his work with the Muppets and The Carpenters probably won’t mean much to most viewers, but has always made it extra-special to me. Had I decided to continue my acting ways chances are I never would have gotten to play a part as fun and devious as Swan, but I like to think it might have been a possibility.

Coming Next

The Devil Don't Wear No Shoes!