Yesterday afternoon I had 15 minutes to kill before my bus was due, so I decided to stop in at my neighborhood toy store to see if it had anything new and/or interesting available on it shelves. As I walked down one of its aisles my eyes fell upon an item I had read was soon going to be available, but had seemed so fantastic I couldn't bring myself to ever hope I would be able to purchase it by so conventional of means. But there it was, waiting for me at the reasonable cost of just $24.95. As I handed it to the bored teenage cashier I could tell she had no idea why it was so special or why I laughed when she asked me if I needed a gift receipt.

"No," I told her, "this is definitely for me."

Sadly, reality forces me to accept that many of you are reacting to this with the same disinterest as the young woman mentioned above--some of you likely have no clue who these two fellows are. I can come to terms with this only because I know that at least a few of you--the few that count--are currently experiencing the same sense of joy and elation that overcame me as I held these two toys in my hands.

There is something truly wonderful about a world where

Andy Kaufman's infamous wrestling career is immortalized in plastic.

Andy Kaufman's infamous wrestling career is immortalized in plastic.

Beyond my own whimsical need to celebrate the popular culture of my youth, one of the reasons I had no choice but to purchase this item is because it reminds me of a moment in Milos Foreman's film biography about Kaufman, Man on the Moon, that I have always found uniquely moving.

The scene itself marks the moment where Kaufman's career is finally effected by the consequences inherent in creating an act built upon the alienation of his audience, but that's not why I find it so affecting. No, the reason I found it so moving when I first saw the film and whenever I've watched it since, is because it marked the very first time Jerry "The King" Lawler acknowledged that their "feud", which culminated in what many regard as one of the greatest moments in television history (see below), was nothing more than an elaborate prank.

This in itself did not amount to any kind of shocking revelation. Anyone at all familiar with Kaufman's career or the realities of professional wrestling knew that it was nothing more than a work of ingenious performance art and nothing close to a genuine battle between two mismatched rivals. Plus, Bob Zmuda, Kaufman's writing and performing partner, admitted as much months earlier in the book he had published about the comedian in time for the movie's release.

But still it was significant because it was the first time Lawler himself gave the game away. For nearly two decades he kept the joke as both a tribute to Kaufman and the once-proud tradition of his art known as kayfabe (the term used by wrestlers for the practice of never letting the marks know what was real and what wasn't). He had even gone so far as recreate the prank with Jim Carrey, causing several credulous media outlets to report that the actor (who in inspired Kaufman fashioned was photographed wearing a neck brace off the set) had been injured at the hands of the wrestler during the filming of their scenes together. His decision then to appear in the above scene was one not lightly made, as it marked the true end of a wonderful pop culture fantasy.

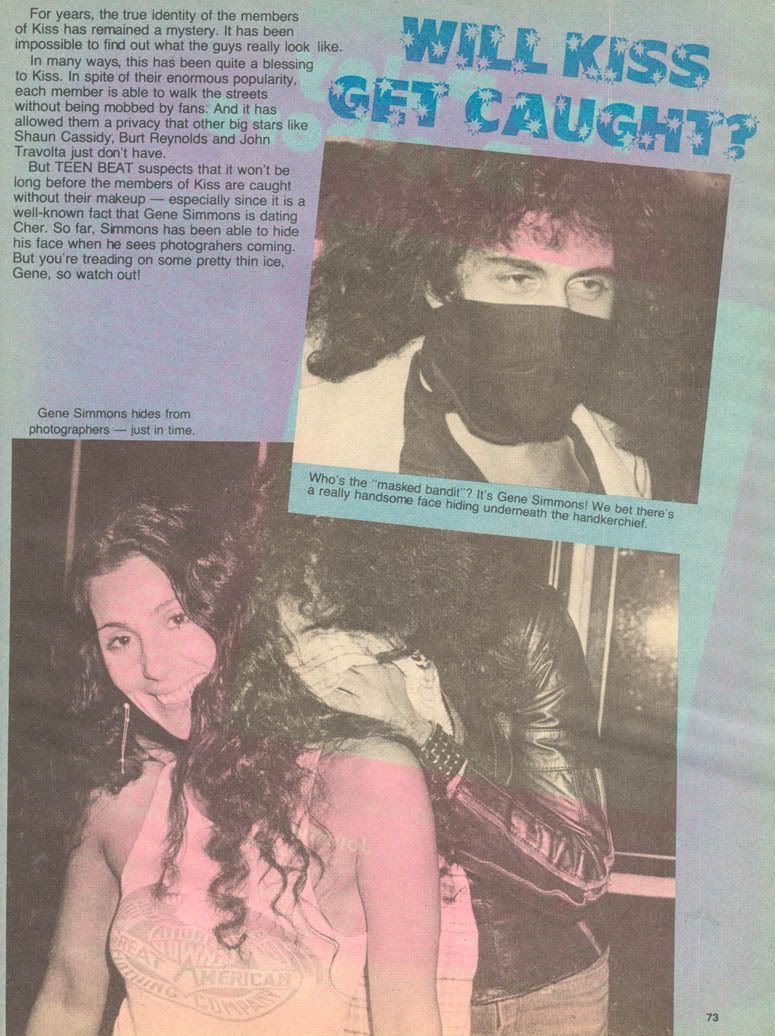

It occurred to me that the ability to keep this kind of secret is something we have sacrificed in the age of the internet and post-modern awareness. Do you remember how in the 1970s the members of Kiss were NEVER photographed without their makeup? Both Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley understood that part of their band's allure was their larger-than-life mystique and that being seen without their makeup would make them seem all-too-human. Fast forward 30 years later and we now know what Simmons looks like in footy pajamas. I recognize that no fantasy can remain unspoiled forever, but were Kiss to come out today, chances are their first single would have barely hit radio stations before someone posted a paparazzi photo of the four of them without makeup (I had thought this theory might be undone by the existence of the group Slipknot, but it took me literally two seconds to find a photo of that group without their masks on).

It occurred to me that the ability to keep this kind of secret is something we have sacrificed in the age of the internet and post-modern awareness. Do you remember how in the 1970s the members of Kiss were NEVER photographed without their makeup? Both Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley understood that part of their band's allure was their larger-than-life mystique and that being seen without their makeup would make them seem all-too-human. Fast forward 30 years later and we now know what Simmons looks like in footy pajamas. I recognize that no fantasy can remain unspoiled forever, but were Kiss to come out today, chances are their first single would have barely hit radio stations before someone posted a paparazzi photo of the four of them without makeup (I had thought this theory might be undone by the existence of the group Slipknot, but it took me literally two seconds to find a photo of that group without their masks on). We still live in a world were pranks like the one propagated by Kaufman and Lawler are possible, but instead of remaining controversial decades after the fact, they are now exposed, examined and dismissed within hours of their occurring. Whereas Kaufman's legend came from his ability to so effectively blur the lines of artifice and reality, today you'll have trouble finding someone willing to admit that those lines even exist. For reasons I can't express, this makes me sad, but luckily this sadness is easily overcome by the existence of toys found within only a few blocks from my house.